For Me the Blockade has Ended

Efrem Shteinbok, 1954. This photo was taken shortly after the graduation from the Leningrad Shipwright University.

The summer of 1941 started out peacefully. I was 13 years old and exams were over. I finished fifth year with perfect marks. (Prior to the Second World War, the first year of classes began at age 8). My mother got a job at the knitting factory in the Krasnoe Selo, near Duderhof (now Mozhayskoe), where we rented a dacha (summer cabin).

On June 15th or 16th, I met my close friend Musya Zapolsky. Musya lived in the apartment next to mine with his father, as his mother had been arrested and deported to the concentration camp in 1937. She was one of the victims of Stalin’s repressions. Musya had already distinguished himself among us with his sober assessment of events and independent thought. We discussed the message that had recently been released by the TASS (Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union) on June 14 about the «next war between Germany and the Soviet Union”, as well as the upcoming summer vacation.

The message stated that no war would occur and as a result not only ordinary people were misled, but military personnel as well. Musya told me that in a few days, he and his grandmother would go to her residence in Western Belarus near Bialystok for the summer. Musya’s grandmother lived in the part of Belarus, which after the civil war became part of Poland. In 1939, this area became Soviet. This allowed Musya’s grandmother, who had never met her grandson before to come visit him in Leningrad in April of 1941. After a 2 month stay she was getting ready to take her grandson to Belarus so he could stay there for the rest of the summer. How could we predict that this would be our last meeting? They left on June 19. Musya’s father did not receive any messages from them. Bialystok was taken by German forces in the first days of the war. Musya went straight into the hands of the Nazis. All the Jews were herded into ghettos and exterminated during the summer.

My mother and I went to our dacha on June 18. Each morning my mother went to work in the Krasnoe Selo, while I ran the household, got acquainted with the neighbourhood children and explored the surrounding area. My father continued his work in Leningrad, while Yasha, my older brother, a student at the Polytechnic University, had his first industrial practicum at the factory «Electrosila».

Our house in Duderhof was located at the foot of Crow Mountain. Crow Mountain is a 150m hill covered in ancient and beautiful vegetation. As it turns out Crow Mountain would be of great strategic importance for the Germans who turned it into an observation post for the shelling of Leningrad, as well as for the Soviet army, when they liberated one of the beautiful cultural places in the world–Peterhof.

Our relaxing stay did not last very long. Neither our house nor the neighbouring ones had a radio. We only learned about current events from my father, who would sometimes come by the dacha in the evening.

June 22, started off as a regular Sunday. Mom slept in a little later than on weekdays, and I rode around on my neighbours bicycle. My father came that day after 1pm. He seemed agitated. Upon entering the house, all he said was: «War.»

It turns out that at 12 o’clock the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the USSR V. Molotov spoke on the all-Union radio. He said that the Germans had crossed the border, without a declaration of war, and German planes had already bombed several cities of the USSR. On the same day the mobilization of reservists born between 1905 — 1918 was announced. During the war conscription widened to include all men born between 1891-1927.

We boys, of course, did not take this news the same way our parents did. Our parents generation had already experienced the First World War and the Civil War. At that time, my father was already a man of retirement age. He knew that hard times were ahead. His eldest son was a student, and the youngest was a schoolboy.

Starting on June 24th, the Government Information Bureau (Sovinformburo) began broadcasting. The population received messages only through its reports, but since these reports were heavily censored, they were often cryptic. One day, the Sovinformburo would broadcast a message about the front aligning near Pskov, a town around 300km away from Leningrad. Then unexpectedly near the town of Luga, which was only about 140km away. The people learned how to sift the truth from these reports, understanding that the Germans were advancing.

On the following Sunday, June 29, we had already run from our cottage back to our home on Puskinskaya Street in Leningrad, leaving all the furniture we had brought to the cottage behind. Getting off the train at Baltic station the first thing I noticed were the giant air balloons. They were set over large and important objects such as St. Isaac’s Cathedral in order to protect them from being targeted by German bombers. Pilots not only risked getting caught on the balloons themselves, but also the ropes tying the balloons to the ground, and the explosive charges that were attached to those ropes.

Leningrad was preparing to defend itself. In late June, additional defences were being constructed around the town of Luga. Ditches were dug, a stockade was built and gun emplacements were constructed. The work was completed mainly by women and students.

At night the city was plunged into darkness, due to a strict mandate requiring all lights to be covered. All approaches to Leningrad were blocked off by stockades- concrete and metal structures that impeded the movement of tanks. The ground floors of the buildings were filled with sand bags and all windows were boarded up. In addition, corner buildings on intersections were transformed into fortified bunkers for machine guns. Anti-aircraft guns were installed on the roofs of many buildings and the attics were supplied with boxes of sand to extinguish incendiary bombs.

The evacuation of children began in early July. Most were evacuated around 150-200 km towards Moscow. The evacuation however, was unsuccessful. The Germans quickly conquered these areas forcing the children to run back to Leningrad. The older ones could go by themselves and some of the younger children were rescued by their parents. Many of the children were captured by the Germans. My future wife, Geta, was evacuated to Staraya Russa together with her kindergarten class. Her father was able to reach her and bring her back to Leningrad using any means of transportation he could find. My friend Isaac Yudbarovsky was able to return to Leningrad just in time. I, too, was prepared for this evacuation and given a buzz cut. The day before departure, I happened to fall on the cobblestones in the backyard, injuring my knee so my parents forbade me from leaving.

After the Germans took Pskov, rumours spread throughout Leningrad describing treachery within the upper echelons of the military.

In mid-July, a rationing system for the distribution of food products was implemented due to food shortages. Hunger had not yet begun, so people just viewed this new system as an inconvenience they had to adjust to. Soon after the card system was implemented, all the shops that sold high quality foods which had been opened after the Russo-Finish War were shut down.

During this period, the relocation of military plants and their employees as well as evacuation of the general populace began.

On July 28, my brother was drafted into the army. My father was very devastated, believing that he would never see his eldest son again.

Due to his age, my father was not eligible for military service. My parents, like many other people, could not decide whether to evacuate. It was tough to leave home and everything familiar within our apartment. Finally, in early August, they applied for evacuation. We began getting ready, packing only essential items. Our departure date was scheduled for August 24, and we had already begun living out of suitcases. Unfortunately the last regular train departed on Aug.23 and our evacuation was cancelled. The Germans had surrounded Leningrad. I found out later that the east-bound train continued to run until August 27th. Only select people were on these last trains, including many of the railwaymen’s families. My friend’s Leo Paritzky family was one of these. We were trapped in the besieged city of Leningrad.

September 8 the Germans took Shlissel’burg completing their ring around the city. The only means of communication between the surrounded city and the mainland was across Lake Ladoga.

Around the end of August the weather was beautiful and there was still food. Most people did not realize what awaited us. Every afternoon on Pushkinskaya Street there was an ice-cream truck and children came running from all around to buy fruit ice-cream for 7 kopeks each, which many families cooked to make a fruit drink.

School started and I entered 6th grade. Classes did not last very long though. The Germans had reached the outskirts of Leningrad in the area of Srednyaya Rogatka. They began shelling the city. After a couple of days,(around the 6th or 7th of September) bombers started dropping both regular and incendiary bombs on the city. All night people huddled in bomb shelters that were present in the basements of most buildings. Our bomb shelter was equipped with very heavy metal doors, thick metal shutters and a ventilation system. The bombing was daily and air-raid warnings sometimes went off repeatedly during the night. People began to take refuge in the bomb shelters early in the evening, particularly those who couldn’t move quickly. Some people brought their chairs and even sofas, since the benches in the shelters were narrow and difficult to sleep on. Bomb shelters were transformed into public living quarters where people spent long hours, waiting to receive the latest news. School was cancelled «until further notice» due to the bombing. All 6th and 7th grade students were given duties as messengers in various schools and households.

On September 8 about 6-7 pm, the Germans made a powerful bombing attack on Leningrad. On this day there were more than a hundred fires in the city, but the worst result was the burning of the Badaevsky warehouses. This led to the destruction of a large number of products. For a long time the black market sold pieces of blackened sugar. I was on the roof of my house and saw enormous flames and clouds of black smoke. In a few days there was a shortage of products and for the first time people understood that tough times lay ahead.

Many employees of the military plants and hospitals lived and worked onsite with only periodic visits to their families.

To alert residents about dangers related to aerial bombing, huge speakers were installed on the streets. A metronome was hooked up to the speaker systems and the speed signified the type of danger. Fast tempo meant bombing was taking place somewhere in the city, while slow tempo signified a reprieve.

Every neighbourhood in Leningrad had its own radio station. When shelling began, it would be announced at the radio station that was located in the neighbourhood that was being targeted. Since shelling occurred from the west, there were warning signs posted on the east side of some streets as follows: “Citizens, this side of the street is more dangerous during artillery fire.» A memorial plaque now hangs outside house 14 on the Nevsky Prospect, warning about the dangers of this side of the street.

September 19th was a beautiful sunny day. I was on duty as an orderly at school (it was about 6:00 pm). My school was located on the Nevsky Prospekt (then Prospect October 25) in the courtyard of the “Coliseum Cinema.” The main duties of orderlies consisted of completing small tasks assigned by teachers such as fetching requested items, or passing on news to other people. Our table was on the first floor near the window at the end of a long corridor that passed through the entire school. Phone lines throughout the city had already been disabled. An air raid warning rang out. The sounds of exploding flak became louder and louder. At the suggestion of a teacher we went down to the bomb shelter. After a few minutes the walls and floor around me began to shake. When we went upstairs, we were shocked by a vision of destruction. A bomb had fallen into the courtyard of the school in front of the window, where we had just been sitting. The entire window frame was knocked out, and the table we had been sitting at was at the other end of the corridor. Our teacher had clearly made the right decision. Exiting onto the street, I became aware that a bomber had broken through into the center of the city and destroyed part of the Kuibyshev Hospital as well as one annex of house 63, a residential building on the Nevsky Prospect. The scariest part for me however, was when people were talking about a bombing that had occurred in the center of Dmitrovsky Lane. In the courtyard of 11 Dmitrovsky Lane was the plant where my father worked, and I knew that at that time he was on duty. I ran there, but the neighborhood was cordoned off and nobody was allowed inside. My mother was extremely worried until my father returned home late that night. The explosion at Dmitrovsky Lane was so strong that a huge crater was created in the center of the street. The buildings surrounding the crater were so damaged, that it took many years after the wars conclusion to restore them. According to unconfirmed rumors, the plane which broke through into the center of the city on a clear sunny was piloted by a female ace. (in general, downtown was rarely reached during the day by German pilots).

A few days later I had to go through the horror again. I was an orderly in a household, when the air-raid siren went off. I stood at the gate of our house. Anti-aircraft guns thundered, trying to prevent the breakthrough of German planes. Suddenly, anti-aircraft shell shrapnel stuck in a wooden manhole cover next to me. Only later was I able to comprehend how lucky I was.

One bomb destroyed the house 4 on Mayakovsky street. The entire building was destroyed except for one lateral load-bearing wall that was adjacent to house 6. A bicycle hung on the 5th floor of this wall. It hung there throughout the entire war, since getting to it was impossible. In some cases, a bomb destroyed the lower floors of buildings, while the top remained intact creating a grisly arch.

Gradually, food supplies began to diminish. Twice my father and I were chosen to collect anything we could find (dirty roots or twigs) from already barren fields. The month of October, is when things began to get very difficult.

As the food supply deteriorated, people within the city began to use bomb shelters less and less, despite incessant bombardment, the main task became to get food. The streets around the Kuznechnyy market became a «black market». People went there to exchange valuables and family heirlooms for food products. The market was run by various undesirables that had access to food supplies.

Dad traded one of our valuables to the janitor at home 27 on Svechnoy Lane for a small bag of bran that was intended to feed horses. Mom bartered other heirlooms for hard cakes made from pomace, the leftover remains of fruit or seeds after the oil had been pressed out. We also made food out of wood glue, eating the skin.

Since my mother and father worked, the simple tasks involved with running the household were left to me. Every family tried to get a «burjuyka» by any means possible. This mini-oven proved its worth after the Civil War. It prepared food, heated the room and exhaust gases were routed through a tube out the window. Throughout the war, people used everything possible for fuel. Furniture, books, boards from destroyed buildings, etc.

The situation in Leningrad was complicated by the fact that there were around 300,000 refugees in Leningrad that had fled the areas surrounding the city.

Power plants operated intermittently due to a lack of fuel. Electricity production stopped periodically at first, then completely. Trams and trolleybuses stopped moving.

After power outages apartments were lit first by candles, and then improvised oil lamps. Kerosene or any other flammable liquid was poured into a glass jar, and then lit. Wood splinters were usually used as wicks.

The water pressure in pipes became very weak. Water had to be taken from standpipes, building service laundries or the Neva River.

During the autumn, rations of bread and other products steadily declined, reaching a minimum on the 20th of November. Working individuals had ration cards that allowed them to have 250g of bread a day, while civilians got 125g. These rules were enforced until December 25. It should be noted that more than half of the breads ingredients were made up of inedible substances such as sawdust.

In November, first men, and then women, started dying of hunger. Burying them was not always possible so bodies were left lying on the street. The first time I saw the dead, was when several corpses wrapped in sheets were lying near the fence of the 36th clinic on Mayakovsky Street.

My future wife Geta, who was then 4 years old, was sleeping in the same bed as her dying father. Her mother during that time was at work (in the barracks).

All the hardships of hunger were intensified by the cold that had descended on Leningrad. The winter was much colder than usual, repeating the record breaking temperatures experienced in 1939-1940 when Russia was at war with Finland. Then, at least, the houses were heated and food was abundant but now, people needed outdoor clothing even within their homes. The worst was when people had to spend the night in a queue mostly with no results.

Sewage poured directly into the courtyard, gradually forming a huge frozen mountain.

Shelling and bombing of the city continued. Air raids sirens associated with the bombardment of the city were now sometimes delayed by 5-6 hours. People now barely paid attention to them continuing to go about their business since bombs were no longer the main threat, hunger was.

I don’t remember why, but during one air raid I had to go to my friend Boris Pripstein’s house on 39 Nekrasov Street. We were sitting at the table when suddenly without a sound the chandelier began to shake. Due to experience; we realized that there had been an explosion nearby. As it turned out, the bomb destroyed building 43, which was only 2 houses down. The street was littered with the wreckage of this house.

On Dec. 25th bread rations were increased to 350 g for workers and 200 g for dependents, but in fact, the bread supply had practically been depleted, not to mention the supply of other products. At 4 or 5 am I got up and wrapped in as many layers as possible, went to stand in line for the bakery on the corner of Nevsky Prospekt and Vosstaniya Street. People in line were cold, but there was no place to take shelter. After standing in line for around 4 hours the baker told us to go home since no bread had been supplied. Sometimes, bakeries wouldn’t even open.

In December, death from starvation became commonplace. People could hardly walk, and if they fell, they couldn’t get up and would just die on the streets. Snow was no longer being cleared from the streets and in many places it was half a meter thick or more. If a house was burning and firefighters attempted to put it out with water, then ice in that area would be even thicker. House 9 on Puskinskaya Street for example, was surrounded by ice more than a meter thick.

Crime within the city began to increase. There were organized groups of people that robbed citizens of bread cards and attacked vans containing bread. Cannibalism began to appear. It was dangerous for a person that did not look emaciated to be on the streets. My mother-in-law told me that one day she was carrying baby Geta across the river Neva. Suddenly she felt the sleigh become lighter. She turned around and saw that two men had grabbed Geta and were attempting to escape. She then had to fight for the life of her child. Thankfully, she was able to rip Geta out of their arms.

During this time, I became depressed. There was nothing to eat. I had no desire to live anymore. Only the warm-heartedness and care of my parents improved my condition. In addition, despite all the problems, city leaders were able to host a kids party for the new year of 1942. At the club CAEH (Children’s Art Education House) a new year’s tree was erected, a small concert was held, and most importantly, we were treated to dinner.

In January, I had a few classes. They were held in the same bomb shelter that 4 months ago had saved my life. The room was terribly cold. There were only 5-7 of us on any given day. Among them were my friends Alex Katz, Nina Belova and Tanya Birshtein, who later became a well-known Russian physicist, Honoured Scientist of Russia, and winner of the International Prize L ‘Oreal-UNESCO «Women in Science».

In the city, we all knew that the «Road to Salvation» was about to be opened on Lake Ladoga. In all likelihood, the products being shipped across Lake Ladoga were not being sent to shops because they had to be accumulated before being distributed. During this period, the second phase of the evacuation of the population began across the ice of Lake Ladoga. The same trucks that brought food products into the city started evacuating the people of Leningrad. The evacuation included many organizations and their staff. My lone uncle, who had been disabled since childhood, was among the evacuees.

At the end of January, my father became bedridden and never recovered. He was slowly fading.

Once upon a time our apartment was large and communal with two entrances, a grand staircase leading to the street, and a back staircase leading to the courtyard. In the 1930’s the apartment was divided. Our family received a separate flat with a courtyard entrance while the rest of the apartment remained communal. In one of the rooms of the communal apartment lived the family of my father’s sister (my aunt Khasya). In January, her son and husband passed away leaving her alone with her oldest son Ilya. He was not serving in the army because he had extremely poor vision.

Finally, on the evening of February 11, 1942 a radio transmission announced that the following day, February 12, all stores would issue food products according to ration cards. The entire city rejoiced!

On the morning of the next day, all the shops were filled with people. I was able to bring back the staple foods our family relied on: millet, oil and sugar. My mother immediately began to cook millet porridge. Our joy was short-lived however. My aunt Khasya barged into the apartment crying, telling us that while her son was standing in line, all of his ration cards had been stolen. This meant certain death. I then got a lesson that I have remembered all my life. My father rose up as best he could on the bed and turned to my mother: «Share with my sister.» These were his last words. My mother fairly divided the food products between our families. The next night my father died.

My mother and I really did not want my father to be taken by soldiers of the Local Air Defense. They would come and take his body to a collection point (usually a hospital morgue). We decided to bury him. With great difficulty, we were able to convince the baker to give us the next day’s bread ration to pay the gravediggers in addition to this we had to add some money to get them to dig. I don’t remember who helped us get the coffin out of the apartment and into the courtyard. My cousin and I tied the coffin to a pair of children’s skis so we could pull it across the snow. My mother and aunt trailed behind us, barely having the strength to walk. The «Expedition» was not easy. The roads were full of debris. We had to walk Ligosvkaya Street and Rasstannaya Street (a long distance from our home).

As we dragged the sleigh through the alleys of the cemetery, we saw several huge piles of corpses. The bodies were in impossible positions and poses. So many dead were brought to the cemetery, that there wasn’t enough time to bury them. The gravediggers led us to a grave that had already been dug. The actual process of lowering the coffin into the grave and filling it with frozen earth was very quick. My mother cried softly and I tried to comfort her.

We then walked slowly home. I scanned the surrounding area, trying to remember the route to the grave. It was very hard to do – the alleys of corpses and ice seemed identical. To my great regret, in the spring, after the death of my mother, I could not find the burial place of my father in the Volkovskoe cemetery. After a while, I realized, or maybe someone suggested to me, that the grave had been dug in advance on purpose. After we left, the gravediggers could take out the coffin, throw the body of my father into the pile and use the tomb for the temporary burial of other bodies. The gravediggers repeated this cycle constantly. These people, or rather, non-humans, profited off the mountains of dead citizens of Leningrad

My mother was extremely distressed, constantly repeating «I can’t live without your father, I just can’t,» but life went on. My mother worked at home, receiving material from her company and sewing uniforms for soldiers (something many women did at the time) and I helped when I could.

When late spring came, the city authorities made a tough, but correct decision. Every citizen had to participate in the cleanup of the city (otherwise an epidemic could break out). Since my mother didn’t have the physical strength to do this work, I went in her place to clear the third Soviet street and get rid of the frozen dirt in our yard.

In mid-April, 5 tram routes started running and several public bath houses opened their doors. I was so happy to be able to accompany my friend to a bathhouse on the First Soviet Street. We washed each other’s backs with low pressure, lukewarm water. The people started gaining confidence. We had experienced a terrible winter and hoped that things would now become easier.

The distribution of food from stores started becoming regular. New products began appearing in the country that people had never seen before such as melange (egg powder), lard and a number of others. These products were introduced into the country under Lend-Lease (an American aid program).

Organizations that treated malnourished workers began to give out coupons for an enhanced diet that lasted 20 days. On May 1, my mother received one of these coupons. Food distribution was organized at the restaurant «Moscow». After the May holidays, I started my third and, as it turned out, last bit of education at school for that year. The main difference between this phase of study and the others consisted of the fact that students had the opportunity to buy soup for 4 cents (boiled water with a spoon of flavouring). Although it was basic, we were glad to have anything.

My mother only went to restaurant “Moscow” for 4-5 days. From the new and abundant food, she got bloody diarrhea, which was impossible to stop. I brought my mother’s meals to our house. She had become bedridden. On the morning of May 13th, she began to wheeze, trying to tell me something but she didn’t have the strength. She died that day at noon. The apartment no longer had anyone in it. I began to knock on the wall of the adjacent apartment and my aunt and cousin immediately came to my apartment. They weren’t able to help. I wept for the first time since the war began. This is how I became an orphan.

After 2 days the hearse arrived. I wrapped my mother’s body in her best wool dress even though I was told that it would be removed anyway. My mother was taken to the Piskarevskoye cemetery which at the time was not yet a memorial cemetery. Enormous trenches had been dug for mass graves, and I know which one contains my mother. Every year on May 13, I visited the cemetery and left roses on the marble slab. My mother’s name was Rose.

After my mother died, I started living with my aunt, trying to help her with everything she needed. For the next week (until May 20), I continued to eat at the restaurant «Moscow» using my mother’s coupons.

That spring shelling became more frequent. On the 15th or 16th of May, around 5:00 pm, I was returning home from a restaurant on the odd side of the Nevsky Prospekt near the Moscow railway station. A route 12 or 13 tram was turning onto the Nevsky Prospect at the same time (tramlines were removed from the Nevsky Prospect in 1949). The tram, which was full of people, got hit by a shell and exploded. I helped lift the twisted pieces of the railcar off trapped people and helped to drag the injured onto the sidewalk close to the pharmacy. For hours the Nevsky Prospect was a bloody mess. The experience was horrifying and sticks with me to this day.

My aunt was a practical woman. She told me to look for herbs (nettle and quinoa) and cooked soup from the herbs I found. It was delicious (the first greens I had eaten that year).

During the winter, even when my dad was sick, we were not particularly concerned about money. The only place to spend it was on our minimal rations, and for this, we had plenty. Now I was relying on my aunt. One day, I collected 2 bags of books from my apartment that I thought were of high quality, and then slowly made my way down the Nevsky Prospect. I sat down on the steps of building 58 (building 58 became LHSTP — Leningrad House of Scientific and Technical Propaganda after the war) and began to sell books. Not many people were interested, and the few that actually bought books were mostly military personnel. Even so I still managed to earn a little bit of money.

Ever since my mother’s death, I had been using ration bread cards with coupons that were meant for the following day. The saleswoman now refused to sell me any more bread, until I began using coupons for the current day. I had to do something. We decided to buy a loaf of bread from black marketeers. Aunt Khasya managed to collect the required money. Through her acquaintances, my aunt found out where she could meet with a middleman. I went to a house on the corner of Sadovaya Street and Mayorov Prospect (now Voznesenskiy Prospect) to meet him. I gave him 400 roubles and got one loaf of bread in return. On my way home, I absentmindedly started pinching off and eating small pieces of bread. When I discovered this, I burst into tears for the second time during the war. I was very ashamed. What could I tell my aunt? She had gathered a large sum of money for bread and I had eaten part of it. But my aunt forgave me.

My cousin Ilya worked in a dairy (№ 2 or number 3, I can’t remember which). The plant had been closed down throughout the entire winter. In the spring, the city began receiving some raw materials, electricity production resumed and water started flowing though the pipes. Ilya, who at the time was the only engineer-technologist at the plant, was able to arrange the production of certain products from powdered milk.

Since May, when navigation had begun on Lake Ladoga, the third stage of the evacuation had been taking place. Now the government issued a decree requiring the mandatory evacuation of women with young children and all people who could not aid in the defence of the city. I was one of the people that fell under these categories. My landlord constantly reminded me that I needed to evacuate. Since I was a minor however, I couldn’t evacuate on my own. I was offered a chance to evacuate with the trade school or children’s home. I didn’t like either of these options and didn’t know what to do.

Before the war, I was a hardworking and successful student. In addition, I attended several school clubs, most of which, had to do with literature. I had a very good relationship with the head of the club, Zoya, who also ran the library (unfortunately I can’t remember Zoya’s last name). One day we ran into each other, and I had the chance to tell her about everything that had happened to me. She told me that she had been talking with a military author who was looking for orphans to help them out with various tasks. Zoye gave me his address. The writer lived in the hotel «Astoria». I promptly set out to meet him. The man was named Alexander Shtein. Alexander would go on to become a famous playwright, authoring plays such as «The Ocean» and «Hotel Astoria » among others. At the time however, he wore a naval uniform and worked at the «Krasnyy Flot» newspaper. We sat together all evening. Alexander asked me various questions and treated me to tea. In parting, he gave me an unusually expensive gift — a few onions. At our next meeting, we discussed my fate again, in particular, how I would be smuggled out of the city, but due to my poor health (I had severe dystrophy), the matter was dropped.

Efrem Shteinbok on his 80th birthday in 2008.

At around the same time, I received a message from my brother. His division was undergoing reorganization in Vologda. I relayed this information to Stein. He said that he would help make documents that would allow me to travel independently to Vologda and get me assigned to a military unit. Stein would give me the documents at our next meeting. When I came, I saw that there was a young woman sitting in the room. I was dumbstruck. It was a well-known poet named Olga Bergholz. Everyone who lived through the blockade knew her name well. She often performed on the radio in order to raise our spirits. I would remember that evening for the rest of my life. We sat together, drank tea, and talked. Alexander Shtein gave me a letter to the military commander of Vologda, and we warmly said our farewells.

Later, I was pleased to know that the inscription on the Piskarevskoye memorial cemetery was based on the texts of Olga Bergholz. In 1942 she wrote «February Diary» and «Leningrad poem.» Alexander Stein and I met again in 1974. It was in January on the evening that had been dedicated to the 30th anniversary of the lifting of the blockade. We had a pleasant conversation and he introduced me to the hostess of the evening Vera Ketlinskaya. Olga Bergholz did not attend at the time; she was very ill and passed away a year later.

For about 2 weeks I prepared for evacuation. I received the document from Alexander Shtein and almost simultaneously my brother managed to petition the military commandant of Vologda to send me permission to visit the city. Because of the documents I received from Stein and Vologda’s commandant, I was issued documents that allowed me to evacuate the city and travel to Vologda. (evacuation to Vologda was not allowed without special permission).

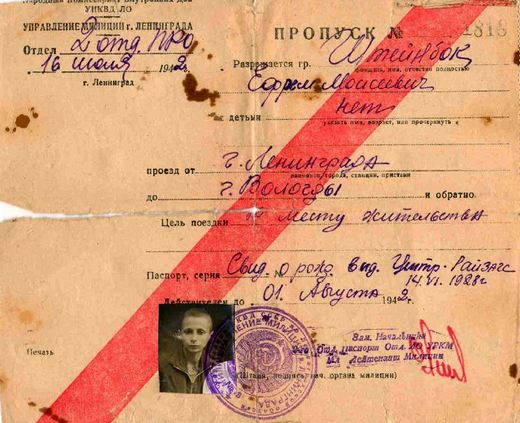

A copy of my pass to Vologda

I inventoried the property within my apartment, which was witnessed by the caretakers of the household. They sealed the apartment in my presence. To replace my ration cards, I received food stamps, and a small lunch box.

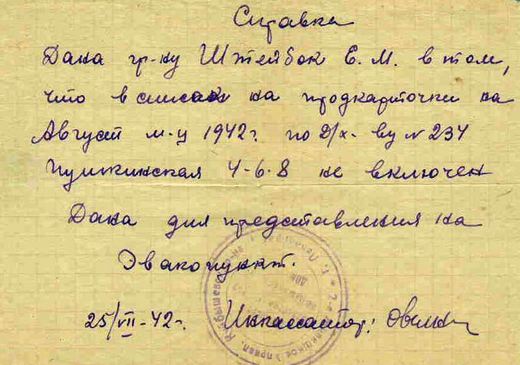

Proof of exchange of ration cards for the food stamps

Proof that I had been removed from the food ration list

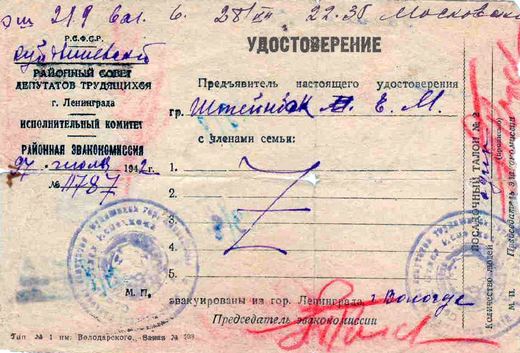

Proof of Evacuation

On July 28, after saying farewell to aunt Khasya and Ilya, I went to the Moscovcky terminal railway station and took the train on the ring road for the Karelian Isthmus. The final stop was Borisova Griva station. Evacuees were then driven down to the Osinovets pier where one large and one small ship were waiting for us. I ended up embarking onto the large one. The small boat never reached its destination. It was bombed enroute by the German air force. The boat took us to the Kobona pier, which was located on the southeast side of Lake Ladoga. Here we were fed, and then moved onto a freight train, heading east. Almost all the major stations on the way to Vologda were evacuation centers where we were fed hearty and rich foods. This turned out to be harmful to most evacuees. Many people died on the road, since their frail bodies couldn’t handle this type of heavy food after being emaciated for so long. For me, the blockade had come to an end.

P.S. My cousin Ilya was conscripted into the army in the fall of 1942. In the summer of 1943 my aunt received a “pohoronka” which was a standard official letter informing her of Ilya’s death. For a long time aunt Khasya did not accept that Ilya had been killed and for years after the war, refused to receive the allowance she was owed as the mother of a deceased Red Army member.

The blockade was breached by Soviet troops on Jan. 18, 1943. A complete lift of the blockade occurred on Jan. 27, 1944. The amount of people killed during the blockade varied between 700 thousand to a million according to different sources. I know that among them were three of my classmates — Victor Dudin, Jura Shmidov and Eugene Sidorov.

Edited by Aaron Wolfman

www.eng.world-war.ru