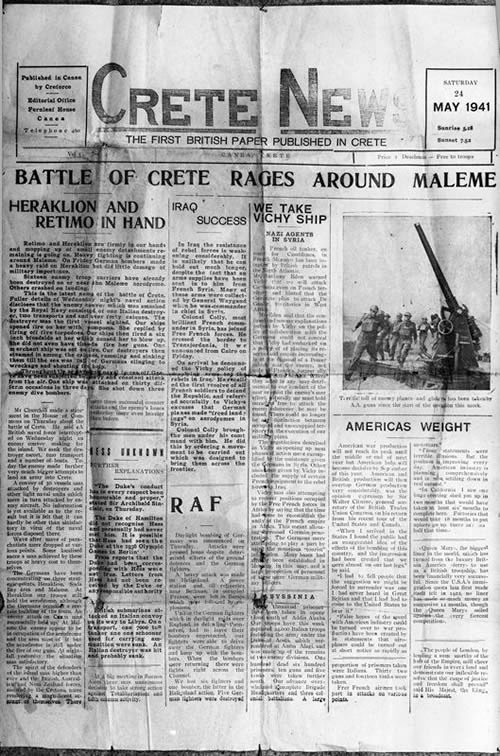

The invasion of Crete – battle for Maleme

Day two – 21 May 1941: battle for Maleme

On 21 May the Germans discovered that the New Zealanders defending Maleme airfield had withdrawn. They were able to consolidate their hold on the airfield and fly in reinforcements. A German attempt to land troops on Crete by sea was foiled when the Royal Navy intercepted the convoy before it was able to reach the coast. New Zealand units near Maleme attempted to recapture the airfield.

Germans occupy Maleme

In Athens, General Kurt Student, commander of the German ground forces on Crete, decided to commit his meagre reserves at Maleme – the sector where the most progress had been made on the first day. All remaining airborne reserves would be dropped in the area while the Luftwaffe (German air force) pounded nearby New Zealand positions. Once the airfield was secure, a battalion of mountain troops would be flown in.

At the same time, a German convoy – 1st Motor Sailing Flotilla – carrying reinforcements and heavy equipment was ordered toward Maleme. Slowed by strong headwinds, the convoy was intercepted by a force of British cruisers and destroyers 29 km north of Canea. Many of the small troop transports were sunk. The heavy losses prompted the Germans to recall a second invasion flotilla to Greece.

The situation changed dramatically overnight. As dawn broke the Germans discovered, to their delight, that the New Zealanders had withdrawn from the airfield and the vital heights of Point 107. They wasted no time in taking advantage of this. With the airfield still under artillery fire, the first transport planes began lumbering in that afternoon, carrying much needed reinforcements (a battalion of mountain troops). The airfield was soon littered with wrecked and damaged aircraft, but enough troops were landed to tip the balance of the battle.

Counter-attack planned

Freyberg realised that if the airfield was not recaptured, Creforce was doomed. A conference of senior New Zealand and Australian commanders decided to launch a counter-attack on the airfield that night. Despite the need for an aggressive response, concerns about a possible sea invasion hampered the operation. Only two battalions – 20th and 28th (Maori) – were assigned to the task, and they were instructed not to move until 20th Battalion had been relieved by an Australian unit. The New Zealanders also faced the prospect of advancing 6 km from the start line to the airfield across rough terrain at night in order to avoid air attacks.

Day three – 22 May 1941: counter-attack fails

On 22 May communication and other problems crippled the planned British counter-attack on the Maleme airfield. The Germans consolidated their position by flying in more troops and supplies. The Allies were forced to withdraw from Maleme and form a new front line near the village of Platanias.

New Zealanders launch counter-attack

The New Zealand counter-attack went wrong from the beginning. The Australian battalion relieving 20th Battalion was held up by German bombing. This delayed the launch of the operation by four hours – a fatal setback, given the need for the airfield to be in New Zealand hands before daylight exposed the troops to attack from the air.

When the attack finally began the New Zealanders pressed forward with great determination. Fierce fighting broke out as the troops ran into pockets of German defenders. With little time to organise set-piece attacks, these positions were rushed using improvised frontal charges. For his part in these actions, platoon commander Second Lieutenant Charles Upham would later be awarded the VC.

By dawn elements of 20th Battalion had reached the eastern edge of the airfield but were unable to move further because of heavy air attacks. Māori troops had fought their way to the village of Pirgos – 2 km from the airfield – but were pinned down by machine-gun and mortar fire. During the afternoon it became clear that no further progress could be made; the New Zealanders were forced to retire to the position they had started from. With the failure of the counter-attack the initiative passed back to the Germans. They lost no time in seizing it.

Withdrawal

At Creforce HQ, Freyberg waited anxiously for news from Maleme. By mid-afternoon it was clear that the counter-attack had failed. The Germans were now free to use the airfield to pour in reinforcements and supplies. As these fresh troops arrived, 5th Brigade’s position became increasingly vulnerable. German units pushing along the southern flank of the New Zealand positions threatened to link up with those concentrated in the Prison Valley. If this were to happen 5th Brigade would be cut off from the rest of Creforce.

Realising the potential danger, Brigadier Edward Puttick, commander of the 2nd New Zealand Division, telephoned Freyberg to urge that 5th Brigade be withdrawn. Freyberg agreed and the New Zealanders pulled back to a new defensive line near Platanias, 6 km east of Maleme.

Day four – 23 May 1941: securing the line

On 23 May the bulk of the New Zealand forces around Maleme airfield retreated to a new defensive line at Platanias. This position was soon threatened by fresh German forces moving in from the south and the New Zealanders were forced back toward Galatas.

New defensive line

By mid-morning on the 23rd the majority of 5th (NZ) Brigade had reached the new defensive line near Platanias. The Germans made several probing raids against 28th (Maori) Battalion units holding the bridge into the village. Supporting fire from Australian artillery ensured that the Germans were unable to mount a concentrated attack on the bridge, but as the day wore on it became apparent that they were attempting to outflank the New Zealanders from the south. Once again 5th Brigade was in danger of being cut off. The decision was made to pull the brigade back to a position east of Galatas.

Alarmingly, the two major German forces – Group West moving east from Maleme and Prison Valley and Group Centre advancing west from the vicinity of Canea – were now only hours away from joining up. Once this occurred they would be in a position to launch an assault on Galatas.

Supply problems

By 23 May supply shortages were becoming a serious problem for Creforce. Troops in the Suda Bay, Retimo and Heraklion sectors only had food rations for another 10 to 14 days – and this calculation was based on men receiving two-thirds rations. Even if more supplies could be landed, distributing them would be difficult. Creforce’s commander, Major-General Bernard Freyberg, had 271 trucks, carrier vehicles and ambulances available to service more than 40,000 troops – and this meagre number was constantly decreasing through air attacks and the lack of repair facilities. Supply difficulties were further exacerbated by the state of the roads and the presence of enemy troops.

Day five – 24 May 1941: Germans press forward

As British forces braced themselves for a German onslaught against Galatas, the Suda Bay, Retimo and Heraklion sectors suffered ferocious air attacks. While the Germans could now replenish supplies and land men with ease, Creforce and its provisions were being depleted rapidly.

Germans advance on Galatas

Reinforced with fresh mountain troops landed at Maleme, the Germans continued to move forward cautiously toward Galatas. General Julius Ringel, now commanding Group West and Group Centre – renamed Ringel Group – favoured a conservative approach. He ordered his forces to consolidate the positions they had secured. Units on the left flank would push forward until level with Platanias. Those in the centre and on the right were ordered to move towards the Canea–Alikianou road and the Galatas heights to meet up with paratroops moving in from the west.

While the Germans advanced cautiously, New Zealand units in the Galatas area reorganised themselves. The 4th (NZ) Brigade took up a defensive position surrounding Galatas village. There was no major attack, but several small skirmishes took place as German reconnaissance patrols probed the New Zealand line.

For Brigadier Edward Puttick, commander of 2nd New Zealand Division, the situation was looking increasingly bleak. He was running short of ammunition and plagued by communication and transport problems. More significantly, his units were being steadily depleted each day – by 24 May around 20% of the New Zealand Division had become casualties.

Suda, Retimo and Heraklion

The Suda Bay area suffered heavy German air attacks and Canea was reduced to burning ruins. Further east, Heraklion was bombed intermittently throughout the day. German paratroops landed during the morning but were not able to secure the airfield. More encouragingly, Creforce received some air support from the Royal Air Force (RAF) that day – five Hurricane fighters operating from North Africa strafed German positions at Heraklion, and eight Wellington bombers attacked Maleme that night. But these operations were too small-scale to challenge Luftwaffe (German air force) control of the air or to disrupt German troop movements.

Day six – 25 May 1941: a black day at Galatas

Galatas was captured by the Germans. A determined counter-attack by New Zealand troops retook the village that night but the reoccupation was short-lived. In the Canea area British troops had to be withdrawn in order to maintain a shortened defensive line. The day’s events convinced Freyberg that an organised withdrawal of his forces was now his only option.

Attack on Galatas

By 25 May the Germans were in position to launch a concerted assault on the Galatas–Canea front. General Ringel issued orders for a two-pronged attack. Two battalions of mountain troops were tasked with seizing the village of Alikianou – 8 km south-west of Galatas – and pushing on toward Suda Bay, where they were to cut the road between Canea and Retimo. The main thrust of the German attack, however, would be carried out by elements of the 100th Mountain Regiment and the (Parachute) Assault Regiment. The former were ordered to capture Galatas and the high ground to the south of the village; the latter would attack the northern edge of the village.

Those defending the Galatas line awaited the inevitable German attack with a sense of unease. On the main front the Germans had positioned several battalions of relatively fresh troops, supported by artillery and aircraft. Against this powerful force the weakened New Zealand Division was only able to deploy the half-strength 18th Battalion, which was down to around 400 men (normal battalion strength was about 780). The remainder of the line was manned by makeshift non-infantry formations.

Pressure on the line

The expected attack did not occur that morning. Instead the New Zealanders were subjected to continued bombardment from German mortars, artillery and aircraft. The shelling reached a peak in the early afternoon and was followed by the first probing attacks by German infantry. Soon all the units near Galatas were under attack. As the afternoon wore on the New Zealanders’ situation became increasingly desperate. Platoons and companies held on as long as they could, but the weight of German numbers forced them back.

With the line in danger of collapsing, 4th Brigade’s commander, Brigadier Lindsay Inglis, threw 23rd Battalion into the front line. The situation at this point was desperate – the only reserves available to Inglis were an infantry company (around 120–140 men) and whatever men he could scrape together from Brigade HQ. He set about getting the latter organised and a motley force, including members of the brigade’s band and the Kiwi Concert Party, moved into an improvised line north of Galatas. Once the first elements of the 23rd Battalion arrived and took up their positions the New Zealanders were able to re-establish a continuous front from Galatas to the sea.

Further south the pressure intensified against the units holding the vital position of Pink Hill, which overlooked the main road into Galatas. By early evening, most of the defenders in this area had withdrawn east of the village. A small covering force – 40 or 50 men – of New Zealand gunners and infantry repelled continuous attacks until they too were forced back, having suffered heavy casualties. The defence of Pink Hill was an important feature of the day’s fighting. The New Zealanders’ stubborn rearguard action blunted the German attack and gave 4th Brigade time to reorganise itself.

New Zealand counter-attack

As the New Zealanders withdrew, the Germans wasted no time in occupying Galatas. Colonel Howard Kippenberger, commanding 10th (NZ) Brigade, realised that if the village was not retaken it would become a jumping-off point for an attack on the New Zealand line. So when two light tanks from the British 7th Royal Tank Regiment arrived that evening, Kippenberger quickly formulated plans for a counter-attack.

[Lieutenant] Farran stopped and spoke to me and I told him to go into the village and see what was there. He clattered off [in the tanks] and we could hear him firing briskly, when two more companies of the Twenty-third arrived … each about eighty strong. They halted on the road near me. The men looked tired, but fit to fight and resolute… . I told the two company commanders they would have to retake Galatos with the help of the two tanks… . The men fixed bayonets and waited grimly.

Kippenberger placed the remnants of 18th Battalion on the eastern edge of Galatas. At the same time, two companies from 23rd Battalion fixed bayonets and moved into position on either side of the road into the village. The plan was simple: each company would attack on their side of the road behind the two tanks.

The tanks set off just after 8 p.m., followed by the infantry. They were soon under fire from all sides. Rather than stopping and clearing each house, the New Zealanders raced through the village to the main square. There they found the tanks: one was knocked out, the other damaged. Under heavy fire from the other side of the square, the men charged. The action was brutal – much of the fighting was at close quarters with bayonets and rifle butts – and the Germans withdrew in disarray. Reinforced by 18th Battalion, the New Zealanders pressed forward. When the fighting died down, the Germans had been pushed back to the south-west corner of the village.

Despite the success of the counter-attack the decision was made to withdraw from Galatas. The New Zealanders did not have the resources to hold the village – a lack of men, artillery and air support had left the defending troops exhausted. There was also concern that the Luftwaffe (German air force) would begin bombing Galatas. With many civilians still inside the village, it was considered an unacceptable risk for the New Zealanders to remain there. In order to maintain an unbroken defensive line, Puttick ordered his forward brigades to withdraw and set up a new line west of Canea.

Day ten — 29 May 1941: awaiting evacuation

As the remnants of Creforce retreated across Crete’s Askifou Plain, the first ships left Sfakia for Egypt. The Germans finally entered Retimo, forcing most of its Australian defenders to surrender. The garrison at Heraklion was evacuated by sea but their convoy suffered heavy losses from German air attacks.

Evacuation plans at Sfakia

Major-General E.C. Weston met with his senior commanders for the first time since the withdrawal began to discuss the final stages of the evacuation. It was decided that 4th (NZ) Brigade would set up a defensive screen at the southern end of the Askifou Plain and make its way to the beaches at nightfall. The 5th (NZ) Brigade would move further south near the village of Komitadhes – some 5 km from Sfakia – before heading for the beaches. The New Zealanders would be followed by 19th (Australian) Brigade and a Royal Marine battalion. The assumption was that the evacuation would be completed on the night of 30 May.

During the afternoon 23rd Battalion, defending the northern entrance to the Askifou Plain, came into contact with leading elements of the pursuing German force. Short on rations and water, the New Zealanders held off several attacks before pulling back to join the remainder of 5th Brigade near Komitadhes. They were closely followed by German troops.

Retimo and Heraklion

By evening advanced elements of the main German force had entered Retimo. The outlook for the Australian defenders was bleak. Fast running out of food and ammunition, they remained unaware of the plan to evacuate to the south. When the garrison surrendered next day, most of one Australian battalion – 2/11th Battalion – dispersed into the surrounding hills.

Further east an evacuation was successfully carried out at Heraklion during the night. A force of two cruisers and six destroyers sailed from Egypt and managed to embark around 4000 British troops. Delayed by a damaged ship, the convoy came under air attack on the return voyage to Alexandria. The German aircraft inflicted serious damage, and many of the rescued troops were killed on the tightly-packed ships.

Continue reading.

Source: http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/war/the-battle-for-crete