The Spirit of the Boys’ Generation

The first time I saw my father’s letters when I was a child, they were in the house of my grandmother, Evdokia Ignatievna Serebryakova. The letters were put in a long kid glove with cut up fingers. The glove was narrow and the letters were folded into tubes. To be honest, that time I was more interested in the glove and I liked to stroke the soft and thin leather. The letters attracted me because the way they were folded was strange. They were folded into triangles and it was the first origami for me. I liked to fold and unfold them. Grandmother didn’t tell me anything about what was in the letters. I knew only that the postcard with the picture of lilies-of-the-valley, which was brighter than other uninteresting yellowed letters, was received 4 years after my grandmother got two “killed-in-action” notifications.

Years later my sister Katya scanned these letters and I typed the text. We managed to do this without having to “decode” them because all the letters were handwritten very legibly. I learned from them that my father was a senior military clerk. Obviously, his writing and literacy helped him in this position.

I was very excited to read these letters. These letters contained the spirit of a boys’ generation, of boys who had stepped in one movement from school desks into the hell of war. In each letter we find great respect and love for parents, pain of separation and happiness at finding family and gratitude to them for their care and love.

In each of my father’s letters, there is some kind of attempt to support his family and friends, to cheer them up, to give hope for a future reunion. Sometimes he warmly recalls the past, sometimes he remembers events with sense of shame and sometimes he looks back at them differently with respect to the ordeals he has experienced. In some letters I imagine a boy who has just left the school, who loves sweets and is interested in his classmates. In other letters there is a mature adult who had gone through all the terrors of war. Unshakeable faith in victory, humour and optimism resound in his letters. I have read aloud some lines from these letters during commemorative meetings on the anniversary of the Great Patriotic War in the university where I taught. Our students, who seemed to be careless and negligent, listened to these moving words, written by a person of their own age from the past with rapt attention and the eyes of some even filled with tears.

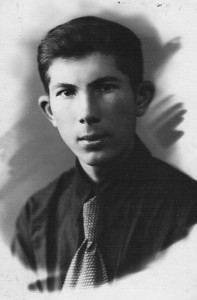

Father left school in 1940. He entered the Railway Institute and Aviation Academy. He passed his exams, but didn’t pass the medical board inspection. On 1 October, he received his call-up paper. It was the first wave of recruitment for 18 year olds — before that only men 21 and older had been drafted.

On 18 October, my father took a picture with his parents and this photograph has always been hung in a frame on the wall in my grandparent’s home. On the 20th of October he set off to his assigned destination. He thought, “Winter-summer, winter–summer and I’ll be back home!” But he only returned 6 years later. And his letters flew all over the country.

On the way to my unit

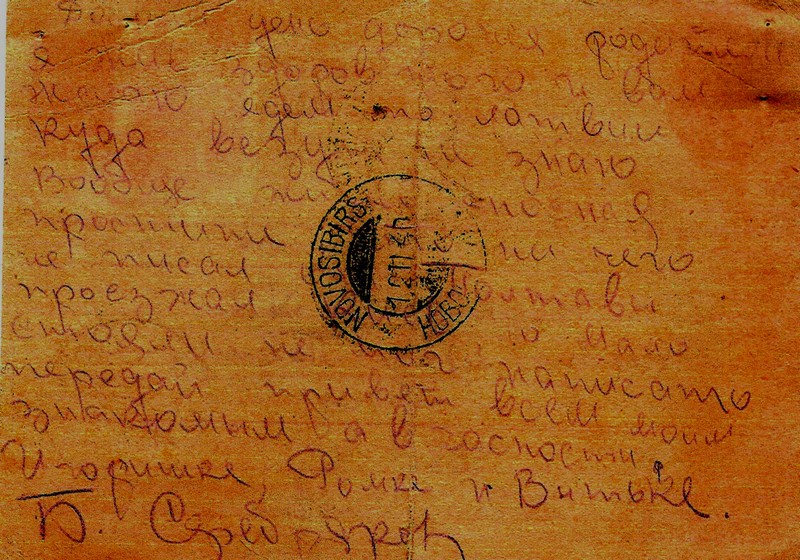

Postcard from Dvinsk dated November 2, 1940

Hello, dear parents, I am safe and sound and I wish the same for you. We are going through Latvia — I don’t know where they are taking us. But on the whole, life is so-so, sorry for not writing you from Poltava, we passed by… and didn’t stop for long, I couldn’t write. Say hello to all my friends and especially to Igoriska, Romka and Vitka.

B. Serebryakov.

Letter dated November 3, 1940

Hello, dear parents, I am safe and sound and I wish the same for you. Today, 03.11.40. I sent a postcard to you but I can’t write much in it. I really beg you to forgive me for not writing from Poltava, because the stops were too short and they didn’t allow us to go out of the carriage during the long stops. In Kiev we stopped while passing though and there wasn’t any mailbox nearby. We set off from Kiev, I have no idea where we are heading. Now people say that we are going to Lithuania, but we don’t know exactly where. Soviet money isn’t used here, there are lats and centimes. Life is good. Everything is very… some say that you can exchange Soviet money at banks. I’ll write when I know more. I’m fine, but tired of the road. Well, I have to go now, 15 minutes left before the train departs. Say hello to Lisa, Misha, Ivan, aunt Agasha, Nyura and Kolya. Well, for now, all the best, I won’t write until I reach my destination, but as soon as I arrive at my unit I’ll send my new address immediately. Congratulations on November 7.

That’s all for now. All the best.

Kisses.

Your son, B. Serebryakov.

From peaceful service

Letter dated December 1, 1940

Hello, my dear parents, I’m sending you my sincere Red Army greetings. In the first lines of my letter I want to tell you that I’m safe and sound and I wish you the same. I am in the army 26 days already and have almost become used to the order of the day. I wonder whether my letters reach you or not because my fellow-countrymen have already recieved letters, as for example, Vladimir Barkovsky and some of the other guys from Novosibirsk, but I have received nothing. A letter from Novosibirsk to Alitus arrives within 10 days and I sent mine together with them. I’m fine, but I worry about your silence. I assume that you have been to the Barkovskys, as they inquire for me in Vladimir’s letter, whether we are together or not. Vladimir and I are in the same battalion but in different companies, and live in the same barracks. We often see each other and I have someone to talk to in my spare time. Today is the first cold day, but there is no snow yet. Your probably already have such a frost that one can’t go outside wearing only a shirt. Here we do morning exercises outside wearing only army issue tanktops and it isn’t so cold. Actually I wonder if Igor and the guys have come to see you?

Dear parents, days fly like hours and hours fly like minutes because we’re training all the time. I cope perfectly well with the material we’re taught. My dear parents I beg you, please, don’t worry much about me. My health doesn’t let me down. The food is good, but there isn’t much sugar — it’s only enough for one serving and nothing’s left for a second helping. So I would like to ask you to send me a little. Soviet money is used there and I would like to ask you to send me a little bit for butter, at least, because they sell butter at our food stand, ten rubles a kilogram. And if I only buy a kilogram a month, it’ll be a luxury because eating the same food all the time gets really boring. The cheese and butter are good, but we’re a bit hard up for sugar. We get it sometimes, but rarely and I don’t have any time to stand in a queue. Actually, I have already asked you, but I’m reminding you once again, if it is possible for you to please send some woolen socks because we won’t be given deerskin boots and soon we’ll go on patrol duty and standing in boots with only foot cloth will be difficult.

I really want to ask you to tell me all the news about everything that has happened in your life since I have been gone. Please, tell me about Greta and her puppy. Is the puppy alive? What did you name him? He’ll be a good dog, I guess. Well, so far, there’s nothing more for me to tell. Sasha Nemkin is serving with me in the same battalion, but in another company. Tolya Karnaukhov and Yura Rudov were transferred, I don’t know where. We were separated in Kiev and they were shipped out in another direction. Well, so far, all the best.

Your son B. Serebryakov. December 1, 1940.

Say hello to all my relatives and friends.

Letter from Alytus, Latvia, dated April 3, 1941

Hi from Olita.

Hello, dear parents, I am safe and sound and I wish the same for you. I received the letter you wrote me 12.03.1941 yesterday and today I’m responding immediately. I’m very happy that you’re all safe and sound and cheerful. For there is nothing to be sad about. I’m not serving in the imperial army, but I pay my debt to my people as I ought to, there’s no other way. Dear father, you write that I think about Kolya Snegirev when I drive. Dad, you’re right, I keep singing that song over and over. You implore me not to give up, but have I ever given up when I was home? Never. Tomorrow will be exactly 5 months since I began my service in the army. It seems like yesterday I got my uniform but I’ll have to get a new one by May. It’s nothing, I don’t have much left of my service, just 76 weeks and after that, take me to my motherland — Novosibirsk! Dad, you can drink to my health but I will not be able to do drink for you, not even with beer. Well, okay then, I’ll smoke a pipe to your health, this is one of the pleasures the army hasn’t prohibited. Thank you very much for your congratulations on my birthday.

My dear beloved mother, I have reproach you a bit – getting sick will not do and you shouldn’t live “quietly” — you need to live a full life because there’s nothing standing in your way. As for the job, I’ll write you the following: do what would make your life easier. As for Eugeniy, I don’t worry about him, but there’s one thing that isn’t so clear for me, how was he wounded? Mom, about Lisa, I’ve been thinking about correspondence with her. I’ve already sent her one letter, but haven’t yet received any reply for some reason. Letters are going extremely slowly, or rather they are delayed at post offices. For example, the letter you wrote 12.03.41 came from Novosibirsk on 14 March and reached Olita on 26 March and I only got it on 02.04.41.

About the job at the shooting range. I think it would be nice to get this job – you would work in summer then rest in winter. Dear mother, you write that I don’t do what I say, but I think I responded appropriately to your letters and except for my response, there is nothing more to write because military life is very monotonous. I got your parcel with tobacco, money, a pen and I’m very grateful for that. I bought butter and sugar with the money you sent and every day I buy myself a half of a loaf of bread and, more than that, I have money to spare for the whole month till May. As for Igor, I’ll say the following: I think he is right in what he’s doing. Let him get as much as possible from life because there is nothing to do in the army compared with civilian life. Let him go out and have a good time, he has been studying for 10 years and hasn’t seen much of life itself. Concerning the weather – it’s warm, no snow, only puddles, the sun comes out more often. I live the old way.

Dear parents, I sent you my certificate [1] long time ago and I don’t know why you still haven’t recieved it. Well, that’s enough for now. Say hello to family and friends.

Kiss you, your son Boris Serebryakov.

I’m writing from our political studies lectures.

From the front

Letter dated August 18, 1941

Hello, dear mother. In the first lines of this letter to Siberia I want to tell you that I am alive and well and wish the same for you. Dear mom, I’d like to know: where is Dad? Has he been mobilized or does he work at the same place he used to? Mom,I’m writing the fourth letter, including a postcard. I haven’t received any reply from you, however, and I cannot understand why. I’m doing well because I work as a senior military clerk in a field hospital. Dear Mom, do not worry much about me, please, for ours is the right cause, the enemy will be defeated. Say hello to all my friends and family. Mommy, please, write me, whether Igor Kabanov has been drafted, or not. If he was, please, find out his address from his mother. Well, that’s it.

Kiss you, Your son, the defender of the sacred motherland, B. Serebryakov.

My address: Active Army, postal field station №515 RFH (Regimental Field Hospital) 136

Serebryakov B.P.

Letter dated October 10, 1941. 00:00 am

A letter to Siberia. From a son of the working people and a son of the motherland.

Hello, dear parents, in the first lines of my letter I want to tell you that I am safe and sound and I wish the same for you. I got the letter you sent on 25 August and I’m responding immediately. Dear parents, I don’t know how to thank you for your letter. I had lost all hope of hearing from my family, but receiving your letter, I hope that we’ll carry on our correspondence as often as possible. Before the 9th I wrote you three letters but I don’t know why you haven’t received them. Yes, I understand that at the moment anything is likely to happen because it’s a hard time now.

Dear parents, today along with your letters I received a letter from Lyudmila Baranova. Thanks that at least my fellow schoolmates still remember me. I’ll scold Igor in letter for not visiting you. What a guy! Is he only our friend during peaceful times or something like that? Or when a friend is on the front, another friend is lying on the stove and the latter one forgets about the family of the first? I’ll tell him off as bad as I can.

Dear parents, recently I got a present sent from Moscow that contained candy, cookies, sausage, cigarettes, cologne and a pair of handkerchiefs with the word “The enemy will be defeated!”

For sure, these wise words of our leaders will come true, there won’t be a pack of fascist dogs left on our territory. Hitler’s plan for blitzkrieg is ruined, Hitler’s dirty pack of dogs will be rolled back and flee, losing their heads as they did during the Patriotic War of 1812 against Napoleon.

The Russian people don’t like uninvited guests and treat them accordingly. Our enemies can’t handle the “gifts” from the Red Army, these surprises are catching them off guard. Our many millions from the young to the old are defending their free life, their one and only motherland – the USSR.

Dear parents, I hope you’re helping the Red Army and serving on the home front as you did during the Finnish War. And do your best in this war as well, work in the factories. Know that by your hard and honest work you’re helping the front and along with the warriors of our Army you’re hastening the collapse of the fascist brutes. Dear parents, tell my cousins if they aren’t drafted, that they should master the art of war and fight. If they’re in the war, send my sincere Komsomol greetings to my brothers and tell them not to spoil the names of our bold Siberian guerrillas who have been fighting against Kolchak’s evil by any acts of cowardice. Tell them not to forget our Siberian patriots Schetinkin, Starodub and many others, including uncle Arsenty Ignatievich Balaba.

I imagine he is still strong and will remember the old times when he was fighting against Kolchak and now will beat the fascist scum.

Well, so far, nothing’s left of worth mentioning. Oh, there’s one thing. Dear parents, most of our friends have already recieved their parcels. So I’d like to ask you to send me, please, warm mittens, preferably woolen and made from leather, and warm socks or foot wrapping and my padded jacket, the one which I used to go skating, and some good tobacco, a small pipe and some candy. If it weighs too much, divide it into two parcels and send the first part and let Igor send the second part.

Well, that’s it. Say hello to family and friends. Komsomol greetings from the front. Kisses, Borya.

Waiting for your reply.

Letter from the hand of Valentin Kozlova, dated September 26, 1941.

Received November 22, 1941 (date written by Boris’s father)

Dear comrade Serebryakov!

I’m writing to you at the request of Boris. He was transferred to another unit. It was on 22 September. I don’t know why he didn’t want to write you. Obviously, he was upset because he didn’t want to leave us. I don’t know his address, but I only know that he is in a rifle regiment and works as military clerk. I’ll try to get you his address if I find it because Borya doesn’t seem to be in a hurry to write you and you’ll worry about him. I worked with him in the same hospital as a nurse. In the event that you’re up to writing me, my address is the same as Borya’s old address, that is: Active Army, postal field station №515 RFH (Regimental Field Hospital) 136, Kozlova Valentina Sergeevna.

I still hope that Boris will write you.

Greetings, your unknown Valya. September 26, 1941

***

After this, the letters stopped coming and father’s parents were given two killed in action notifications, one after another. Grandpa hid the first one from grandma, but failed to hide the second notice. Then they were said that Boris was missing. And there began the years of hope, pending and attempts to find their son.

The following postcard is from Nikolay Yaschenko, the godson of Pavel Petrovich, Boris’s father, who tried to find some information about Boris in the central bureau of losses in Moscow.

***

Postcard from Nikolay Yaschenko dated February 27, 1944.

Dear Pavel Petrovich and aunt Dusya!

I’m in Moscow after my tour in Almaty, got here very comfortably. Tomorrow I’m continuing my way to my unit. As I promised, I was in the bureau of losses and got some information concerning Boris and Vasily: neither Boris nor Vasily are listed on the list of casualties.

I wrote an application to the People’s Commissariat ofDefense of the USSR asking them to clear everything out about Boris and Vasily in the units they had been serving. I also asked once again to double check all the lists. The results will be sent to you, my father and me.

So that’s all that I managed to find out. How is Pavel Petrovich? Is aunt Dusya well? How often does Zhenya visit you? She must be upset, so, please, aunt Dusya, cheer her up. I’ll write the next letter from my unit. Hello to all my relatives and friends, and, the warmest greetings, definitely, to you.

Kisses.

Nikolay Yaschenko

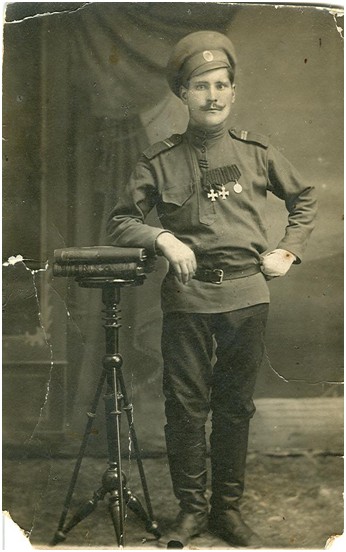

Nikolay Ivanovich Yaschenko (1919 – 2001) was Commander of the 214th Rifle Regiment of the 73rd Rifle Guard Division of the 57th Army, 3rd Ukrainian Front, Guards Major, Hero of the Soviet Union.

[1] Here the young soldier is speaking about his formal contract with the Army that would serve as a document entitling his family for benefits. The actual certificate read thus: »This is to certify that the Red Army soldier, comrade Serebryakov Boris Pavlovich, entered the service of the Red Army as of November 4, 1940. Issued for the eligibility of benefits for the family of comrade Serebryako in accordance with the law of the USSR, valid until October, 1942. (signed) Head Lieutenant Dmitriev.»

Translation into English by Timofeeva Italina and edited by Thomas Hulbert.