US Forces in New Zealand

Introduction

At any one time between June 1942 and mid-1944 there were between 15,000 and 45,000 American servicemen in camp in New Zealand. For both visitors and hosts this was an intriguing experience with much of the quality of a Hollywood fantasy.

The American soldier found himself ‘deep in the heart of the South Seas’, in the words of his army-issue pocket guide. He usually came here either before or immediately after experiencing the horror of war on a Pacific island, and he found a land of milk and honey (literally), of caring mothers and ‘pretty girls’. Little wonder that in later years Leon Uris would write a novel about the experience (Battle cry) and that Hollywood would make a film (Until they sail) with Paul Newman as the heart-throb.

For the host people, now nearly three years into the anxieties and deprivation of wartime, the arrival of thousands of well-fed young Americans with smiles on their faces, charm in their hearts and money in their pockets was like a Hollywood romance come briefly to life. New Zealanders too have recalled the experience in novels and a television drama.

What gave the encounter its special quality was that the two societies were sufficiently similar to communicate easily, but sufficiently different to find each other intriguing. They were former British colonies with a frontier past. Both believed in democracy, civil liberties and the capitalist way of life. Most people in both countries spoke English as their mother tongue. And from December 1941 the similarities became even stronger as the two nations, each with a Pacific coastline, found themselves at war with Japan.

Yet there were also significant differences. The United States was a large and confident society of more than 130 million people, many of whom, a generation before, had been European slum-dwellers or peasants. New Zealand, by contrast, was a small, isolated country with 1.6 million inhabitants, about the population of Detroit, Michigan. It remained in many ways colonial in outlook, a Britain of the South which had some difficulty convincing the new arrivals that it was not ruled by Winston Churchill.

So the ‘American invasion’ (as New Zealanders affectionately called it) brought a considerable clash of cultures. While Kiwi and Yankee spoke the same language, they did so in different accents. Though they shared a fondness for owning cars, they drove them on opposite sides of the road. The meeting of these two cultures – similar, yet different – is the theme of this web feature.

American invasion, 1942-1944

The invasion began in Auckland on 12 June 1942 as five transport ships carrying ‘doughboys’ of the US Army sailed into the harbour. Two days later Marines (‘leathernecks’) landed in Wellington. They had arrived as a result of the outbreak of war in the Pacific six months before. From the New Zealand perspective the Americans strengthened New Zealand’s defences against possible Japanese attack; the Americans saw New Zealand as a valuable source of supply and a staging post for operations against the Japanese in the Pacific.

Visit from the First Lady

Between 28 August and 3 September 1943 New Zealand played host to Eleanor Roosevelt, First Lady of the United States. She came to visit the American forces, inspect the work of the American Red Cross, and study the contribution of New Zealand women to the war effort.

American life in New Zealand between 1942 and 1944 was centred on the camps, most of which were within marching distance or a short train journey from Wellington or Auckland city. Some of the soldiers were here to train for forthcoming battles on Pacific islands. They practised landings and jungle marches. Others had returned from the war and were here for rest and recreation or to recover their health; and there were some whose job was to provide the supplies for a modern army.

The American forces worked hard and men craved time off. But New Zealand leisure habits were very different to American ones. So the visitors devised their own forms of entertainment and established enclaves of American culture. There were games of baseball, jazz concerts, dances, and five Red Cross clubs which offered cheap hamburgers, doughnuts and Coca-Cola.

The presence of thousands of well-paid Americans as part of a large army brought about a minor economic boom in New Zealand and affected local patterns of commerce. Dry cleaners, taxi drivers and milk bars did well; there was increased activity on the wharves; and market gardeners came under pressure to grow more cabbages for the soldiers in the Pacific.

For many people of both nations, the most memorable aspect of the American invasion was the home visits. Often these were arranged formally, with New Zealand families signing up to offer the Americans a weekend at home. New Zealanders generally warmed to their extrovert guests, while the Americans in turn appreciated the home comforts and genuine kindness offered by their hosts.

Romantic liaisons between American servicemen and New Zealand women inevitably developed. The soldiers were starved of female company, and many Kiwi women enjoyed the Americans’ good manners and their offers of taxi rides, ice-cream sodas and flowers. Some 1500 New Zealand women married American servicemen in these years. This was not universally welcomed, especially by Kiwi men, and there were a number of fights and plenty of muttering about the invading ‘bedroom commandos’.

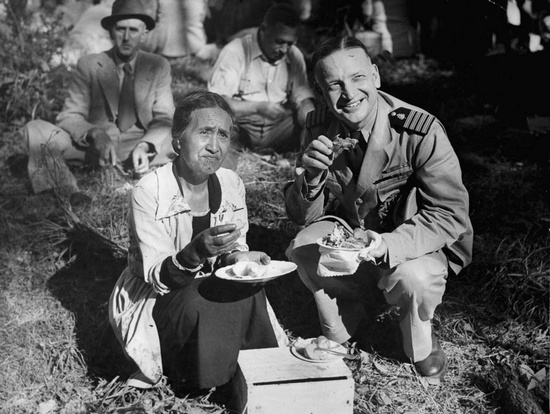

There were also tensions between some American servicemen and Māori. As a result, strenuous efforts were made to build inter-racial bridges – Princess Te Puea arranged a series of visits to Ngāruawāhia in Waikato, and the Americans were also welcomed by Ngāti Pōneke Young Māori Club in Wellington and onto a marae in Gisborne.

The American invasion began to ebb in late 1943. For some New Zealanders it was a relief to see the men go; for others it was an occasion of sadness and, before long, grief as many Americans died, especially in the invasion of Tarawa, in the Gilbert Islands. For both visitors and hosts the ‘brief encounter’ left powerful memories.

The troops arrive

For Aucklanders, the invasion began on 12 June 1942. The skies were grey and the water the colour of steel as five transport ships, with a cruiser in front and a destroyer in the rear, sailed into Auckland Harbour unannounced. The next morning the Mayor of Auckland, J.A.C. Allum, and four military bands stood on Prince’s Wharf waiting to greet the new arrivals. They played appropriate pieces – ‘The Stars and Stripes forever’; ‘Colonel Bogey’ – and were quickly answered by sousaphones onboard ship playing Roll out the barrel. Local ferries blasted their horns, passengers waved; the Americans, nurses in blue, soldiers in olive-green, cheered and crammed the city side of one transport so tightly that the ship listed heavily.

As they berthed, another interesting exchange occurred. The Americans threw down oranges, cigarettes and money; the waiting Kiwis picked up the gifts and threw back New Zealand coins. When some of the visitors wondered where they were, an American on the wharf, one of the advance guard, told them all they needed to know: ‘No Scotch, two per cent beer, but nice folks.’ Some evidently did know what country they had reached, for the first of the newcomers to land on New Zealand soil was Sergeant Nathan E. Cook, chosen in commemoration of the explorer Captain James Cook. It was some hours before all his comrades of the 145th Regiment, 37th Infantry Division were marched off to the railway station and on to camp.

Wellington’s invasion began two days later, on 14 June 1942, when a battered USS Wakefield entered the harbour. It was a Sunday morning and there were few about, but again there was a band waiting on King’s Wharf. This time it played the Marine Corps hymn, ‘From the halls of Montezuma, to the shores of Tripoli…’, for these arrivals were the 1st Marine Division. The distinction – army units to Auckland, Marines to Wellington – was to remain largely (although not exclusively) the pattern as Americans, women as well as men, arrived over the next two years.

Why did they come?

It was the dramatic spread of war to the Pacific some six months earlier which had brought about the first substantial landing in New Zealand of overseas troops since British regiments in the 1860s.

On 7 December 1941 Japanese bombers had crippled the American Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu. If New Zealanders felt vaguely thankful that the Americans were now involved in the war, their confidence was quickly shaken. Within days British naval strength, for so long New Zealand’s surest bastion, was shown to be vulnerable. The warships HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse were sunk by Japanese torpedoes. By Christmas Day Hong Kong had fallen; and then on 15 February 1942 Singapore surrendered. Four days later Darwin was bombed. Some New Zealanders feared that Auckland might be next.

Looking to the US

The Prime Minister, Peter Fraser, appealed to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill for assistance in strengthening New Zealand’s defences. Churchill was sympathetic but in no position to help. The obvious option was to emulate Australia and withdrawing the 2nd New Zealand Division from the Middle East to defend the homeland. But the war in the Middle East was delicately balanced, and the New Zealand troops had been trained to fight there. To withdraw them would be time-consuming and costly in terms of shipping. So on 5 March 1942 Churchill asked Roosevelt to send a division to New Zealand on the condition that the New Zealanders remained in Egypt. Roosevelt agreed, and on 24 March cabled that ‘we are straining every effort’ to send forces as soon as possible.

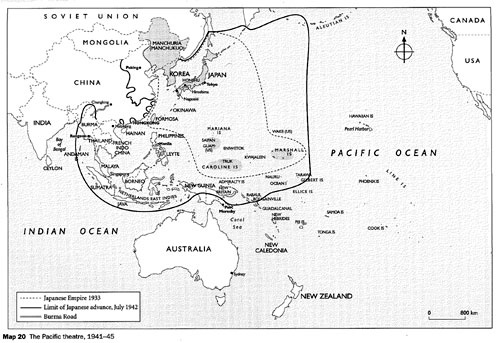

From the American perspective, New Zealand had strategic importance. In mid-March the Allies had decided to divide responsibility for their forces into three zones. The British would control the Middle East–Indian Ocean area, the European–Atlantic zone would be a shared responsibility, and the Pacific would come under the US Joint Chiefs of Staff. The Pacific was divided into two main theatres: the South-west Pacific – including Australia, the Philippines, New Guinea and the Dutch East Indies – and the Pacific Ocean, in which New Zealand was a main base.

New Zealand would thus serve as a source of supply and a staging post for operations against the Japanese in the Pacific. There American forces could train for offensives ahead or recuperate from battles just past. New Zealand could also grow vegetables and provide stores for the forces in the front line.

The camps

American life in New Zealand between 1942 and 1944 was centred on the camps, most of which were within marching distance or a short train journey from Wellington or Auckland city.

In the south, the major area of American settlement was on the Kapiti coast, between the west coast beaches and the mountainous Tararua Ranges. Around Paekākāriki there were three large settlements, Camp Paekakariki, Camp Russell (now in Queen Elizabeth Park) and, on the other side of the highway, Camp McKay (also spelt Mackay). Close by were smaller camps at Pāuatahanui, Judgeford Valley and Titahi Bay. In all, more than 21,000 men could be accommodated in the area.

In Auckland there was a scattering of camps from Pukekohe and Papakura in the south to Mechanics Bay, Western Springs, and various parks on the Auckland isthmus. Here 29,500 could be accommodated. Two other places also hosted the Americans. North of Auckland a number of farm camps were set up in the Warkworth area, while Solway Park in Masterton had beds for some 2400 Marines.

Many of the camp sites were quite small and occupied land that already had memories and associations for New Zealanders. In Wellington, Anderson’s Park where boys had played cricket and Central Park where lovers had strolled were suddenly covered in huts. Hutt Park raceway hosted not horses but American soldiers. Auckland Domain was covered by regular lines of army huts. In both Wellington and Auckland a remarkable number of buildings were used by the Americans. In the capital, Hannahs Building, the Bank of New Zealand, Odlins and Tisdalls served as stores or offices. It was difficult, if you lived in these two centres, not to be aware of the invasion.

Conditions

Camp life seemed spartan for men landing directly from the United States, but comfortable for those arriving from the heat of a Pacific battle. At first most of the Americans lived in pyramid-shaped tents, but increasingly they moved into two-, four- or occasionally eight-man huts. There was often no electric light or heat, and the louvred windows let in the cold and the damp. Men brought up in the central heating of American suburban homes found New Zealand winters unpleasant.

Soldiers lined up with their own mess gear at the cookhouse and ate in mess rooms with bare wooden tables. Food was plentiful, and cooked if possible in American style. But the local staples, especially fatty lamb (‘god-damned mountain-goat’), were not easy for the visitors to cook or to eat. All the larger camps had stores from which American products – cigarettes, Coca-Cola – could be bought. The camps did their best to make the men feel at home amid bush and sandhills.

The camp drill

The first bugle call was at 6 a.m. and the men were at physical drill 10 minutes later. The subsequent routine depended on where they had come from or were headed. Those arriving fresh from the United States were here to be trained for battles on Pacific islands. There were few ceremonial parades in full dress uniform, although all stood to attention at sunset when ‘Old Glory’ was hauled down. There were long route marches to toughen up young city slickers and scouting missions in the Tararua Ranges, which stood in for tropical jungle; artillerymen learnt how to fire under camouflage; landings on Pacific beaches were practised on the Petone foreshore, at Eastbourne, and more ambitiously on Māhia Peninsula, south of Gisborne. When reality finally dawned at Guadalcanal and Tarawa, these practices must have seemed innocent and pleasant by comparison.

Tragedy at Paekākāriki

Wartime censorship meant that newspapers were not permitted to write about the American presence in New Zealand until November 1942, and thereafter the news was strictly controlled. One unfortunate episode never reported was the drowning of 10 United States Navy personnel off the Paekākāriki coast near Wellington in June 1943.

When the horror of the Pacific war got too much, the men might return to New Zealand. Some came simply for what a later generation described as ‘R & R’ (rest and recreation): a period of good food, good times and peace in which the body could recover and the mind let go of its nightmares. Others, less fortunate, returned on stretchers. Some were wounded; more came back suffering the fevers of malaria. In all, 19 hospitals were set up to take almost 10,000 patients. Cornwall Park in Auckland and Silverstream in Wellington were the sites of major institutions. To provide care and the human warmth of a familiar female accent, a considerable number of American nurses came to New Zealand. This was not just a male invasion.

Men too worked at providing the back-up needed by a modern army. The Quartermaster Corps took over large warehouses and areas of the wharves, procured local goods, and packed them off to the war zone. New Zealand conditions added some difficulties. Wet winters, the restricted range of vegetables available and periodic disputes with the ‘wharfies’ were not the least of the problems. Though locals at times muttered about the Americans’ fondness for machinery (they introduced forklifts to New Zealand), all were impressed with their efficiency and thoroughness.

The American forces worked hard and craved time off. But New Zealand leisure habits were very different to American ones. So the visitors devised their own forms of entertainment and established enclaves of American culture. There were games of baseball, jazz concerts, dances, and five Red Cross clubs which offered cheap hamburgers, doughnuts and Coca-Cola.

All dressed up and nowhere to go

Although the American forces in New Zealand worked hard, there had to be some time for fun; and, increasingly, those arriving had come to recover from war and to enjoy rest and recreation. This presented the American authorities with a problem, for New Zealand and American patterns of leisure were different. Many Americans were used to a lively urban culture; New Zealand cities were closed and deserted in the evenings and on Sundays. So the American soldier with a ‘liberty pass’ at first found it difficult to buy the alcohol he desired or the foods he craved. There was nowhere for him to dance to the songs he hummed.

One response was for the Americans to provide their own entertainment and to begin establishing enclaves of American culture in this foreign land. Like most soldiers, the Americans found ways of amusing themselves informally. There was the usual skylarking, teasing and swapping of funny stories; and there was much gambling, usually the games of blackjack and craps.

The Americans also provided their own organised entertainment. Sport was a particular favourite, since it helped to raise morale and improve physical fitness as well as providing enjoyment for spectators. Baseball and softball leagues were organised for weekend afternoons, and a crowd of 20,000 watched a baseball game at Wellington’s Athletic Park in January 1943. Boxing tournaments were held, and an intensely competitive game of American football was played on Eden Park in Auckland between the army and the Marines. In Wellington in mid-1943 an old Wakefield St building was converted into a gymnasium and venue for basketball and badminton. A skating rink was opened nearby.

There were occasional efforts to play sport with the locals. Tugs-of-war appear to have crossed cultural boundaries. On one occasion a game of rugby was played with New Zealanders – causing the Americans much amusement but also some disgust. The American photographer witnessing the performance described it as ‘mayhem’; the apparent object was to twist the opponent’s neck, ‘throw him on the ground, and take the football away from him’. Such occasions of sporting competition between the nations were rare. In general the Americans carried their own games with them.

Music and dance

The Americans also organised music for themselves. Their units were well supplied with bands, and at the larger camps there was a regular weekly concert. Occasionally travelling entertainers arrived to perform. The most famous was the jazz clarinettist Artie Shaw, who came with his navy band. The comedian Joe E. Brown was another popular visitor. If there was no live music available, from April 1944 the doughboys could tune into Radio 1ZM in Auckland, the ‘American Expeditionary Station’, to hear ‘Music America Loves Best’ or ‘American College Songs’.

Most of the bases, especially the hospitals, had photographic darkrooms and materials for painting, drawing and carving. They also offered regular showings of Hollywood movies – outside in ‘starlight theatres’ at the smaller bases, and in the recreation halls at larger camps such as Papakura and McKay. The recreation hall at Titahi Bay still stands. On special occasions the American Red Cross hostesses at the camps would arrange dances to which the ‘right type’ of women were invited as partners.

Red Cross clubs

Red Cross officials, nearly all of them women, organised Red Cross clubs in Warkworth, Masterton, the Hotel Cecil near the Wellington railway station, and two in the Auckland Hotel, one each for officers and men.

These clubs were oases of American culture. There was cheap American food – hamburgers, doughnuts, ice-cream sodas, Coca-Cola, apple pie, coffee. There were a library and desks at which to write home; there were games to play, such as table tennis and pool; and there were facilities for pressing and mending clothes. The American hostesses were supported by New Zealand volunteers, who worked in the canteens and supervised the ‘wholesome’ dances that were put on at these clubs.

Source: http://www.nzhistory.net.nz