A Childhood in Nazi-Occupied Italy

An Account of my life in Italy 1940 — 1946

‘The past is a foreign country, they do things differently there’

‘The Go-Between’ LP Hartley

This is an account of my years in Italy under Nazi occupation and of the series of events that took me there. It is, of course, an account of my own personal experience but I hope it will give some idea of what the Italian people suffered in 1944 in the Fascist Republic of Salò, during the later stages of the Second World War.

Early years in Leeds

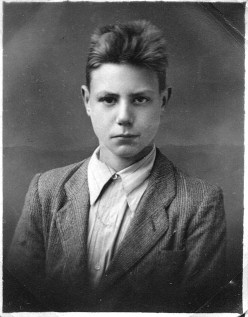

I was born in Leeds on the 9th of June 1930. My father, Pietro Ghiringhelli (known as Rino), was Italian. He came to Leeds in 1919 at the age of 17 to work for his uncle, Peter Maturi, a cutler. Shortly afterwards he met my mother, Elena Granelli. She was born in Leeds in 1905 of Italian parents. They were married in 1928.

My father joined the Italian ‘Fascisti all’Estero’ association (Fascists Abroad) and I can recollect going to social gatherings, around 1936, at the Italian Consul’s office in Bradford. During the Italian invasion of Abyssinia (now better know as Ethiopia) I can remember my mother giving up her gold wedding ring there. To applause, all the married women walked up to a basket and placed their gold wedding rings in it as ‘a gift’ to the Duce, in return they received steel rings (fede d’acciao) with the date and details of the donation inscribed inside it. From 1936 it was not very easy being Italian or having an Italian name; my earliest recollections of nationalism is being held down in the school playground by several boys and made to inhale again and again from a bottle of smelling salts as my mouth was covered. I was about seven when this happened. I remember the injustice of it and the dismissive attitude of the teacher when I told her.

I spent the first nine months of the war in Leeds. I can still distinctly remember Chamberlain’s solemn declaration on the wireless that Britain was at war with Germany. I remember being issued with a gas mask, and gas mask drill at school, and the Anderson air-raid shelter in our garden. This was the period which later became known as the ‘phoney war’, but it didn’t seem phoney then with the blackout strictly imposed, groping about with torches in the dark and cars driving along with the dimmest slit of light from their masked headlamps. Then, early in 1940, I watched newsreels of the French roads blocked with fleeing refugees and, later, the Dunkirk evacuation.

On the 10th of June 1940, a day after my 10th birthday, Mussolini made his ill fated decision to enter the war. The police went into action that very night all over Britain. There was a knock on our door in the late evening and two Special Branch officers came and arrested my father. He was ordered to pack a small suitcase. I remember that we had two photographs on display in the living room, one of Vittorio Emmanuele III, the King of Italy, and the other of the Duce, Benito Mussolini, both in steel helmets. In confiscating them one was smashed. I remember my mother in tears, clearing up the glass from the carpet, after my father had been taken away. We had no telephone and it was only the next morning that we learnt that my maternal grandfather, Ferdinando Granelli, had also been arrested as had other Italians in Leeds and elsewhere. A few days later next of kin were informed that all the arrested men were interned on the Isle of Man. My grandfather was released in 1943, he died in 1945.

Deportation

About three weeks after his arrest, without warning, my father was unexpectedly released under police escort. We were given a few hours to pack one suitcase each and to catch a train to Glasgow; my mother and father, myself and my young sister, Gloria, aged four. The train up north was crowded with soldiers and I remember sitting in the corridor, with a kilted soldier, on his kit bag. The train went right into the Glasgow docks where we got off to board a ship, the Monarch of Bermuda. After a rigorous search, my collection of stamps and an atlas I had just got for my birthday were confiscated and thrown aside. There were 629 of us, led by Giuseppe Bastianini, the Italian Ambassador, a high ranking Fascist who was subsequently made governor of Italian occupied Dalmatia. A senior member of the Fascist Grand Council, Bastianini later played a prominent role in the downfall of Mussolini in July 1943.

From Glasgow we sailed for Lisbon, constantly zigzagging to avoid mined areas and U-boats. I remember there was lots of boat drill, when we were all kept on deck standing in lifebelts for what seemed like hours. No doubt it was necessary given the constant danger, but a little anti-Italian feeling may also have crept in, in dealing with what were enemy nationals; we were treated fairly, but coldly. The crew were no doubt brave merchant seamen charged with an unusual task (one of my own maternal uncles, John Granelli, served with distinction as Second Engineer on the British ship, the SS Sacramento, constantly sailing between Hull and New York throughout the war). On 26 June we arrived in Lisbon. We were not allowed ashore, but were transferred directly to the Conte Rosso, an Italian Lloyd-Triestino liner, which had arrived from Italy with the British Embassy staff and a reciprocal number of expatriate British citizens.

In contrast to the Monarch of Bermuda, on the Conte Rosso we were given first class treatment and the finest food and wines. We were in the dining room when Bastianini and his entourage appeared resplendent in full Fascist uniform. Prior to this I had only glimpsed him in on the Monarch of Bermuda in a drab suit. Bastianini went from table to table, briefly chatting with all of us. Several weeks before the fatal 10th of June I had double-fractured my right arm and it was still in plaster, and it was way past the date for its removal. I can remember Bastianini asking me about it, talking to my parents, and ordering that the plaster be removed the next day; which it was. We arrived at Messina in Sicily where we disembarked. Other than being issued with rail passes, we were now completely on our own.

Arrival in Sicily

One thing has remained vividly in my mind. As we left the ship to go to the sea ferry from Messina to Reggio Calabria, on the Italian mainland, a teenage sun tanned Sicilian boy asked if he could carry our luggage. He was in bare feet with trousers that came down mid calf. We had four heavy leather suitcases packed solid and my father said yes, expecting that he would take two. Instead the boy put a broad leather belt through the handles of two and slung them on his shoulder, then picked up the other two and set off at a trot to the ferry. There he quickly dropped them, was paid, and dashed back for more.

Italy, after only a few days of war, seemed at peace. We stopped off in Rome for a day sightseeing and visited the Vatican. Then we stayed above Santa Maria del Taro, in a hamlet called Pianlavagnolo, behind Chiavari in the Apennine mountains for several weeks, with my mother’s sister’s family. Then by train again to Porto Valtravaglia on Lake Maggiore, to the tiny village of Musadino, where my father was born. News filtered through of the sinking by U-boat (U-47 commanded by the famous Gunther Prien, in the night 1-2 July 1940) of the Andorra Star‘ off Mallin Head, the northernmost point of Ireland. The Andorra Star‘ was bound for Canada, with about 700 interned Italians, most of whom drowned. My father would have almost certainly been on that doomed ship had he not opted for deportation; many of the men he knew were lost. It also brought home to us how lucky we had been to have sailed through the Irish sea, the Bay of Biscay, and the Mediterranean on two ships in wartime without mishap. The Conte Rosso also fared badly, used as a troop ship after we disembarked, it was torpedoed and sunk in 1941 with the loss of 1,212 lives.

My father’s family had settled in France during the 1920s, so the family house in Musadino was empty. There was electricity in the house but no running water; that had to be fetched in buckets from an outside public fountain. The house was sturdy, built in the mid-18th century, on three floors, but there were no inner stairs nor drainage; to get to the first floor (where we lived) you had to ascend a gloomy outside stone staircase; this led to a balcony from which a steep wooden flight of stairs led to the top balcony and a large bedroom. A window facing the outside street was iron barred with inner wooden shutters, the two balconies faced an inner rectangular courtyard, onto which other houses faced. The closet was just a walled in door-less hole, in a corner of the courtyard, over a huge septic tank; when it was full it had to be emptied by hand and the contents were used as fertilizer.

All this hit my mother very hard. We had had a comfortable life in Leeds and, most unusually for those days, we had a fully equipped modern bathroom, a washing machine, and a Hoover vacuum cleaner. Quite apart from having no water my mother couldn’t speak a word of Italian. Disaster struck almost at once. Within a few weeks my father was called up and sent to Yugoslavia, serving mostly in Split (then called Spalato) in Dalmatia.

Starting school

I started school in Italy in the 1st elementary class, which I found totally humiliating. My class mates were all six years old, apart from one seven-year-old boy who had learning difficulties and had to repeat the year. I, as a ten-year-old, towered over them. Moreover, for the first few weeks I had to wear an infantile smock like the rest of them. In class it wasn’t too bad, but at playtime I rapidly became a figure of fun.

It was during this period that something happened which made me a life-long anti-nationalist. I was set upon by a group of lads after school and stoned, the group rapidly growing as more joined in to shouts and yells of ‘Inglese!’ Having been nearly suffocated in England with smelling salts and called ‘eye-tie’, I was now being stoned and called ‘English’. None of the stones hit me, but I ran home feeling rejected and an outcast in both countries.

Following an accident in 1940, I developed an acute double hernia and had to have an operation in Luino, about eight kilometres from Musadino. It must have been a desperate time for my mother, but somehow she coped. Just before my operation my parents came to visit me, my father in full uniform as an infantry soldier. He had finished his training and was bound for Yugoslavia, (although at the time he didn’t know where he was being sent). I didn’t see him again until 8 December 1942, when he was unexpectedly discharged from the army.

This is one date I can accurately pin-point because it was a public holiday, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, when he walked into the house. He should have been home a week or two before, he told us, but the first train he was on was ambushed by Tito’s partisans. The line was blown up and the train was machine gunned. My dad had jumped down from the carriage and lain down on the track behind a train wheel until it was all over.

Following my operation, in early 1941, I was sent to recuperate in Loano, a sea resort in Liguria, at state expense under the auspices of the ‘Gioventù italiana del littorio’ (the Fascist youth organisation). My mother accompanied me to Varese; I was wearing a black shirt and army green shorts, not quite the full Balilla outfit. At the station in Varese I joined several other boys and girls on a train to Genoa, where we changed for Loano. From Genoa the train went slowly past several areas which had been heavily shelled by the British navy (by the battleships Renown and Malaya, and the cruiser Sheffield, on 9 February 1941, I discovered after the war). This was my first sight of heavy war damage, but I was to see plenty of it in the years ahead, culminating in my standing in Hanover’s railway station, as a British soldier in 1948, and seeing the utter devastation of the city for miles around.

At the Loano recuperation centre I first became aware of what a totalitarian state really was. There were several news bulletins a day, and we had to listen to two of them, one at breakfast and one at lunch time. As soon as the martial music began, which preceded the newscast, we all had to rise and stand to attention in silence until the news finished. Then to a teacher’s cry of ‘A chi la vittoria?’ (To whom victory?), to which we all responded with the Fascist salute (known as ‘il saluto romano’) and the shout ‘A noi!’ (To us!), we at last sat down to our meal. All we heard were reports of victories, unprecedented heroism acknowledged by the enemy, and victorious strategic planned retreats in the desert to trap the enemy.

At the time I believed all this, only much later did I learn of the defeats suffered by the Italian army in North Africa. A lot of my new companions were girls, a few of mixed race, from Libya. Apart from the dreaded news bulletins and everything done to a strict timetable, we were treated well. I cannot now remember how long I was there, it could have been three months or perhaps less.

Hunger and cold

When I returned to Musadino I spoke Italian reasonably well and the humiliation of the first elementary class was over. I was put in the 2nd class. By now though, my clothes were beginning to be in tatters and my sister was rapidly outgrowing hers. I had no shoes nor boots, just bare feet in ‘zoccoli’, these were roughly carved wooden soles held on the feet by a leather strap. This was normal village footwear, the only difference being that I didn’t have any socks. My trousers and shirt were patched and re-patched. The winter of 1941 was also the coldest in living memory and at times I used to nearly pass out from cold and hunger. I remember being constantly hungry from 1941 to 1945, although the worst year was 1944. There was a ration system, but seldom were there any goods available to fulfil it in the village.

Milan was only a few miles away, but it might have been a thousand. We passed through in 1940 when we first arrived and visited the Duomo, but Milan had already been bombed, and I didn’t return there until 1945 when I was with the South African Army. It was bombed again several times in 1940, but the really huge devastating raid was in daylight in October 1942. After this we had a stream of refugees, mainly women and children. This had a curious effect on my fortunes — suddenly I was accepted by all the village boys as one of them and the poor Milanese boys became the object of our scorn and taunts. We would taunt them in dialect with ‘Milanaiz, spetascez, mangia scerez, a deëz a deëz’ (‘Milanesi, spetezzatori, mangiate ciliegie dieci alla volta’ — Milanese, farters, eat cherries ten at a time).

It was on 28 October (anniversary of the March on Rome, and the Fascist seizure of power) either 1941 or 1942 (I now forget which) that I saw and took part in a great fascist rally in Porto Valtravaglia. The whole school had to attend in black shirts, ‘Figli e figlie della Lupa’ (‘sons and daughters of the she-wolf’, very young children, the equivalent of cubs), Balilla (boys from 8 to 14), ‘Avanguardisti’ (boys from 15 to 18) were drawn up in ranks together with soldiers of the 7° Reggimento Fanteria (from the local barracks in Porto Valtravaglia near Lucchini glass manufacturers), along the broad lake front, which was festooned with flags and banners. The Balilla (us) were led by teachers who were members of the MVSN (‘Milizia Voluntaria per la sicurezza Nazionale’ — ‘National Voluntary Militia for National Security) and the ‘Avanguardisti’ were led by officers of the MVSN. In Porto Valtravaglia there was a kindly middle aged doctor, Doctor Ballerò, small with a paunch. I was amazed to see him and the local chemist as MVSN officers in full Fascist uniform with their stomachs pulled in by blue cummerbunds.

There was lots of smirking and suppressed giggles amongst my school chums. Another vignette which has stuck in my mind was that, at the end of the parade, we were all, except for the soldiers, marched off to church for a solemn mass and a blessing of the flags. All the flags and banners were held by bearers in full uniform including their fascist ‘fez’ headgear or alpine hats. At first it surprised me to see men wearing hats in church at mass and the priest not complaining about it, but suddenly, and I am fairly sure this is not hindsight, I saw the whole thing as a farce.

My father comes back

Following his discharge from the army my father went to work as a machine grinder in a factory (Ditta Boltri) in Porto Valtravaglia. He worked 10 hours a day, from 6am to 5pm, five and a half days a week. But after that, nearly every day, he and I would go to the mountains to cut wood for fuel or to cultivate three pieces of land we owned. When he returned from the army he discovered that my mother had run up a huge bill at the only village shop and bakery and he paid this off by felling wood after work for the shop owner, it took him months to do so. By now my father’s eyes were opened. He was told by the village men, gradually as they came to trust him, of the Fascist atrocities from 1920 to 1922, when the Fascists took power, and of the second wave of terror in 1925; of the ferocious beatings with the ‘manganello’ (a cudgel like a baseball bat), the doses of castor oil they forced their opponents to drink (about a litre), and the murders. He became strongly anti-fascist and, later, a clandestine member of the Partito Socialista di Unità Proletaria, as the Italian Socialist Party was then called.

A few months after he came home my father went by train to the Po valley rice fields south of Milan to see if he could buy rice. He returned empty handed, and it was the first and last time I saw my father burst into tears. A few weeks after this, desperate for food, he went to the Po valley again. This time he took me with him. We tramped from farm to farm — long, hot, seemingly endless dusty roads. We had many refusals, some polite, some not, some offered to sell us any amount we wanted but at exorbitant prices. Finally we found a farm where we bought rice and maize at a high but reasonable price. The rice was for eating but my father wanted the maize for seed.

The return journey by train was, no doubt, a nightmare for my father but very exciting and enjoyable for me. We finally got on an already crowded train with many people clinging to the sides. We managed to stand on the buffers between two carriages with our suitcases full of rice and maize, I well remember my father clutching me tightly. We stopped at one point and a long train passed by slowly heading south, it appeared to be an entire German division, flat car after flat car loaded with tanks, and on every flat car German steel-helmeted soldiers at the front and back with rifles. This was the first time I saw German soldiers, I was to see many more.

(The armoured division I saw heading south was probably the newly reformed and renamed Panzer-Division ‘Herman Göring, formed from the few survivors of the Division ‘Herman Göring’ in Tunis and scattered elements from France, Holland, and Germany. The new armoured division was worked up in Brittany, France, and then transferred by rail to the Naples area.)

The railway also passed close to a prisoner-of-war camp and I could clearly see British soldiers in khaki in the barbed wire compound. Some waved and I waved back, I thought they were waving to me, but it was probably to young women on the train.

The rice didn’t last long, but my father felled all the mulberry trees on a plot of family land and dug the entire field by hand. He made me dig too but my contribution was very small. The mulberry trees were grown for feeding silk worms, which the women of the area specialised in rearing before the war. (I saw the last season of rearing silk worms in 1940). Every square foot was planted with ‘grano turco’ (maize) and after that we subsisted mainly on ‘polenta’ until 1945. We were always hungry, but my father made sure we didn’t starve. He knew every mushroom and wild plant that you could eat. We caught and ate every kind of animal, every sort of bird. We caught and ate frogs, snails, fresh water shrimp, hedgehogs, and on one occasion, a squirrel. From mid-1943 we also kept guinea pigs, which were another useful supply of protein.

I should also record the great kindness of many people. Like Signora Isabella, the mother of my friends, Amatore and Anita. Her husband had died in 1929 as a result of a severe beating by Fascists. I used to pass her house on my way to the factory and time and time again she would have a bowl of freshly milked goat’s milk for me. Or Virginia, another lady, who occasionally would give me a new laid egg which I would crack and suck raw there and then.

The fall of Mussolini

The fall of Mussolini in July 1943 and the King’s appointment of General Pietro Badoglio as head of a new government, came as a complete surprise. Everybody went absolutely wild for about three days and every Fascist emblem was torn down. Long suppressed political parties sprang into life with a plethora of newspapers.

Badoglio said on the radio that Italy would continue the war alongside Germany, but everyone took that with a pinch of salt. There was great happiness in the belief that the war would soon be over. A phrase from his speech was ‘La guerra continua’ (The war continues) and this phrase stuck in my mind because just about every newspaper headlined it. Mussolini was said to be under arrest in a secret place and it was assumed by all that the Fascists were finished. There was a blaze of red flags everywhere and the Musadino village band brought out their hidden instruments and played for the first time since 1922. The band was headed by a man who had always been very kind to me, but I can only remember his nickname, ‘Corbellin’ (Basket maker), now. He too had been severely beaten by Fascists in the 1920s.

On 1 September news came through that the Allies had crossed unopposed from Sicily to the Italian mainland at Reggio Calabria (where we had arrived in June 1940), and on 8 September 1943 Badoglio announced what had been expected all August, that Italy was unable to continue the war and was seeking an armistice. Then we learnt that Badoglio’s government and the King had fled from Rome. A few days later the Italian garrison in Porto Valtravaglia deserted and the barracks were ransacked. No one stopped the looting which carried on all day. I came home with boots and as much clothing as I could carry. From then on until 1945 I was dressed in a variety of Italian army clothes as were many in the area.

The prisoner-of-war camp I had seen from the train emptied too. Some prisoners were recaptured by the Germans and sent to Germany, but many joined the rapidly forming Italian partisan groups in the mountains and were helped back to Allied lines or to Switzerland. Those that couldn’t get back, I learnt later, stayed on and fought with the partisans until 1945.

Shortly after this the Germans moved in force into Porto Valtravaglia, using the Albergo del Sole, the main hotel, as their headquarters. At this time I was in the 4th elementary class (4th and 5th primary classes were held in Porto Valtravaglia) and I was in Porto Valtravaglia every day. People were absolutely stunned that this had happened but it was still hoped that somehow the war would end.

The Germans seemed to be using Porto Valtravaglia, right on Lake Maggiore, as a leave centre. The lake front was full of them, and they seemed harmless enough in those first few days. They even gave away their left-over soup after their evening meal, when two or three huge soup cauldrons were trundled out and the left-over soup distributed to kids. I went a couple of times with a can until most of our parents told us not to. Then came the shattering news that Mussolini had been rescued by a daring raid of SS paratroopers and that a Republican Fascist party had been formed with such die-hard ultra fascists as the notorious Roberto Farinacci and the fanatical Alessandro Pavolini.

Mussolini tried to reconstitute the Italian army under General Graziani. But the Germans would not allow them to fight the Allies on the front line. Instead they were used against the partisans, freeing up most of the German army to fight at the front. This new Fascist republican army was called La Guardia Nazionale Republicana (GNR) and it now included remnants of the fascist MVSN, now disbanded, as a sub-unit called ‘Corpo di Camice Nere’ (CCN — The Black Shirt Corps). GNR soldiers were indistinguishable from the previous Italian army except for their black shirts and ties. Many of these troops were forced recruits, desertions were high and their performance, from a Fascist point of view, poor, and the inclusion of fanatical Fascists of the CCN pleased neither Graziani nor their leader Renato Ricci. As a consequence, in July 1944 several official but semi-autonomous Fascist groups were formed such as the ‘Brigate Nere’ (the Black Brigades), formed by Pavolini, and ‘La X Mas’ (The 10th MAS), commanded by Juno Valerio Borghese. Of the two the most notorious and murderous were the Brigate Nere. They were noted for their extreme youth, taking recruits from 16 upwards, mostly recruited in central Italy. In addition to these groups there were the Italian SS, this was the ‘Legione SS Italiana’, volunteer ultra-fascists, of the ’29. Waffen-Grenadier-Division der SS (italienische Nr.1)’, commanded by SS-Staf Lombard and SS Brigaf. Hansen, and nationalist Russian Cossack groups, also under German command and operating in north east Italy. The Brigate Nere and La X Mas operated mainly in the area where I lived. In addition there were German SS and rear line support troops who carried out independent patrols.

The Battle of San Martino

Within weeks of the fall of Mussolini one of the very first Partisan battles in Italy took place, now known as the Battle of San Martino. I actually witnessed this battle from my bedroom window in Musadino at the age of thirteen. I was awoken one morning to the distant muffled roar of many trucks and half-tracked vehicles. By now I seldom saw any vehicles, a lorry used to come to the village about once a week but that had long stopped, so the sound of engines was a rare novelty.

The sound was from a German motorised column going up the winding mountain road to San Martino, a small church with a couple of stone summer-grazing houses, but also with concrete strong-points from the First World War (being near the border), the old ‘Cadorna Line’. About the same time Stukas appeared and began to dive-bomb the mountain. When the Stukas finished, machine gun and rifle fire started and continued most of the day before a deafening silence descended on the valley.

The small group of partisans consisted of 10 army officers and 70 Bersaglieri soldiers from the Porto Valtravaglia barracks, together with 20 Allied soldiers from the prisoner-of-war camp I had seen in the Po valley. They had escaped on 8 September but had not managed to get across the Swiss border. This partisan group was known as ‘Gruppo Cinque Giornate’ (The Five Days Group — in commemoration of the ‘Five Days of Milan’, when there was an uprising against the Austrians in 1848). It was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Carlo Croce, his Partisan name was ‘Giustizia’ (Justice), he later crossed back into Italy and died in a later battle.

At the time I did not know this, I got these facts later from the official Italian records which state that the action began ‘on the night between 13—14 November 1943’ and that the Stukas were brought in on the 15th, but my distinct recollection is that it was early morning when it began unless it started whilst I slept. Two thousand Germans took part, plus a battalion of ‘Brigate Nere’ (The Black Brigade). Despite being outnumbered, there was unexpected stiff resistance, and even two aircraft were shot down. Most of the partisans, I learnt later, broke through the cordon to Switzerland during the night of the 15th, leaving about 50 dead. Six partisans were captured and taken to Luino, where after extreme brutal treatment, during a prolonged interrogation, they were shot. A few days after this battle the Germans blew up the small church. When I saw San Martino in June 1945 it was just a pile of rubble.

During this action the younger brother of the village shopkeeper, Benedetto Isabella, had gone up to San Michele to prepare it for when the village cattle were taken up for the summer. There was still heavy snow on the mountain. No one knows exactly what happened, but at the entrance to San Michele there was a German improvised check-point and he was shot through the head. (There is now a memorial stone dedicated to him at the spot where he was murdered). As the hours went by his family were getting concerned when a Fascist militiaman called to officially inform them that he had been shot ‘resisting arrest’ and that the body could be collected the next day where it still lay, before the curfew. I have always been very proud of my father for what happened next. He and several other men of Musadino said enough is enough; they lit torches and climbed the mountain that very night through the snow, in defiance of the strict curfew, and brought his body down on an improvised stretcher taking turns to carry it four at a time. By dawn they were down with him.

The Germans then said that only family members and close friends could attend his funeral, but the whole of Musadino went to it, we boys included, and many more people from the surrounding villages. As his coffin was carried through the village, followed by his relatives on foot, to the next village of Domo, where the church and cemetery was, more and more people just left their houses silently and joined in. The cemetery was full and spilled outside the gates. I don’t think anyone organised it; it was a spontaneous gesture of defiance.

German ‘recruitment’

At age 14, in June 1944, after a short stint working for a builder, I joined my father working in the factory in Porto Valtravaglia. I was put on a lathe making screws. After a few weeks there one morning we got word that the Germans were planning a ‘rastrellamento’ (search and round-up), these subsequently occurred with increasing frequency when workers, from 14 to 50, were rounded up and sent to work in Germany. The order to ‘recruit’ workers for Germany had been made on 3 March 1944, but ‘recruitment’ was a euphemism for being press-ganged without the option of refusing. We poured out of the factory and scrambled up a hill from where we watched the Germans turn up later.

In 1944 things were really bad and I got used to people being shot or disappearing. The way the Germans now behaved seemed senseless to everybody. The bulk of the Italian army was deported to slave labour in Germany and as civilian young men were rounded up for work in Germany more and more saw joining the partisan bands as the only way of escape. But as more joined them the Nazi and Fascist repression became harsher. This was the year of the Italian civil war, the Partisans against the ultra-fascist Republicans with very few prisoners taken on either side. Bands of Fascists seemed almost autonomous and clearly out of control with captured partisans having their eyes gauged out or worse before being shot. The area where we lived now was part of the ‘Republica Sociale Italiana’ (the Italian Social Republic), known as the Republic of Salò, from the small town of Salò on the shores of Lake Garda, where Mussolini now had his headquarters. Ostensibly controlled by Mussolini, the Germans were the real masters.

It was early in this period that I witnessed a bizarre episode. The men of the village used to gather in the village ‘osteria’ to drink wine and play cards; not in the public area at the front but in the inn keeper’s living room at the back. I was there one evening with my father when two German soldiers on patrol entered the public part of the inn, but seeing it deserted came into the back private quarters. They looked middle aged to me. One sat near me and one opposite speaking a few words in broken Italian. One began showing us photos of his children and wife. Then I became aware of an almost whispered argument, in Lombard dialect, with a young man urging that we should kill them and others saying that doing so would only bring disaster on the village. While this was going on I was holding one of the soldiers’ steel helmets and I felt my hands begin to shake. As it happened, nothing came of it, and they left smiling to continue their patrol.

Someone must have tipped off the Fascists about this incident, because one night shortly afterwards the house of the young man who had urged killing the Germans was raided. As they came up the steps he managed to get out of a bedroom window and hang by his hands from the house rafters. He got away after they had left, but I never saw him again.

As partisan activity increased, so the repression tightened. I remember that on our ‘portone’ (a huge wooden double door with a small inset door leading to the inner courtyard) a large printed poster was pasted up in Italian and German listing about 20 points, each one ending ‘… will be punished by death’. The crimes meriting the death penalty, by public hanging, ranged from helping partisans to being caught out after curfew or tearing down posters.

The published order by the German Commandant, General Kesselring, was that for every German killed by partisans 10 Italians selected at random would be shot. Here is just a flavour of many similar public notices: German 5 Corps, 1 S, No. 391, of 9 August 1944: ‘(c) If crimes of outstanding violence are committed, especially against German soldiers, an appropriate number of hostages will be hanged. In such cases the whole population of the place will be assembled to witness the executions. After the bodies have been left hanging for 12 hours, the public will be ordered to bury them without ceremony and without the assistance of any priest.’ (see pages 316-327 of ‘War In Italy 1943-1945 — A Brutal Story’ by Richard Lamb (published by John Murray, 1993) for the full text of this order and many other chilling documents).

Most certainly these were not empty threats, mere bluff and bluster. On 12 August 1944 at Sant’Anna di Stazzema, Lucca, 560 civilians were massacred and on 26 September 31 men were publicly hanged at Bassano del Grappa. These are but two out of many such brutal incidents.

Would I survive the war?

One day I really thought that my luck had run out (by now I didn’t really believe I would survive the war). I was in the courtyard of our house when a member of the Brigate Nere came in, carrying a submachine gun. He was 16, he actually told me his age, and I knew now from experience that these young fanatical thugs were the worst and apt to panic and fire off at the least excuse. He asked me who lived there and I told him. Then I suddenly remembered that when Mussolini fell the year before I had painted ‘W Badoglio!’ (Long Live Badoglio!) on the white wall to the side of our door on the first floor and I thought he might find it, although it was covered with brushwood bundles. Many had been shot for far less than this. He had just started to talk to me, boasting about his age and showing me his dagger and gun, when someone from his group called his name and he and they abruptly left.

On another occasion I was fooling around during a short break in the factory with my work mates, boys my age. We were kicking a ball of paper around between our lathes when I gave it a kick but missed, my wooden ‘zoccolo’ (wooden soled sandal) flew off and I kicked the edge of the lathe stand splitting the gap between my little toe and the next toe. I was in excruciating pain and the men realised I was badly hurt. I was carried to the first aid room and my dad was informed, he held my foot while iodine was poured in the wound to cauterise it after clearing the dirt and grease out. I cannot remember now how I got home, it may have been by horse and cart, but at home a Milanese refugee friend happened to visit me. His name was Amleto and he was about 17 or 18, he had a great influence on me. In return for helping him learn English (I had nearly forgotten it by then) he taught me chess and gave me an abiding interest in astronomy. Because of the blackout then, the skies were wonderful to look at, thousand upon thousand of stars.

When Amleto saw what had happened he offered to take me to Doctor Balerò in Porto on his bike, to see if my injury needed stitching. My mother agreed I should go, and we set off with me sitting on his crossbar. We were nearly in Porto when we ran into a road block. This time there were no smiling middle aged soldiers, it was an SS group, with a GNR member acting as interpreter. We both had our hands up, I sitting on the ground with Amleto standing by my side. We were asked for our identity cards and where we were going. I told them what had happened and my foot was uncovered and inspected. I remember the Italian fascist saying ‘This doesn’t make sense, he would have been taken from the factory not from Musadino’ or words to that effect. I said that it had got worse.

At this point Amleto, seeing things were not going smoothly, pulled out a Republican Fascist party membership card. With that we were immediately let through. But I had told Amleto a lot and I feared having put my father and others in danger. I was stunned and could hardly speak to him. He said to me, ‘Don’t worry, things are not what they seem’, but I didn’t see him again until I was with the South African army in May 1945, when they held a party in the Albergo del Sole in Porto Valtravaglia, to which some prominent Italian resistance fighters, selected by the mayor, were invited. I was stood watching some people dancing when suddenly Amleto appeared by my side in partisan uniform, complete with red communist neck scarf. He told me that he was a member of the Communist Party and that he had been ordered to join the Fascist Republican party for cover, but had rejoined his partisan group after the road block incident in case I had endangered him by telling people that he was a Republican Fascist. I told him I had told no one, but probably I would have done had he returned.

I should explain that before July 1943 nearly everyone had a Fascist party membership card. Mass membership had started in 1932 and continued to grow year by year. The voluntary character of membership all but disappeared when membership became compulsory for all civil servants, both local and central. In the end nearly every worker was a member. After September 1943, even the remnant of members were purged and only extreme fascists were in the ‘Partito Fascista Republicano’. This is why I was startled when Amleto produced his card. In mid 1944 all from the age of 14 were issued with new identity cards which had to be carried at all times. A prominent feature of these new cards was race, all had ‘stirpe ariana’ (Race: Aryan); Jews did not qualify for a card.

Amleto was quite right in saying ‘things are not what they seem’. The reverse of this also happened in Musadino. A house overlooked our courtyard at right angles to us. The top floor of this adjacent house was taken over by a refugee family from Milan, a woman and her two children. Most weekends they were visited by her husband from Milan, a man I only knew as ‘Barbuto’ from the trim beard he had. He always greeted me and others in a very friendly manner and he was reasonably popular in the village. Then in May 1945, with his beard shaved off, he came to live in Musadino permanently, saying that they no longer had a house in the city. Shortly after this he was arrested and taken under escort back to Milan, where after a short trial he was sentenced to 30 years; with the bloodbath at its height he was lucky. It turned out that he was a card carrying member of the Republican Fascist party and had been responsible for quite a few arrests and deaths in Milan. If a Fascist escaped death, sentences like his were fairly common in 1945, but nearly all but extreme cases were amnestied or commuted in 1948 and later.

War now seemed to me like normal life. Another incident which is clear in my mind happened when I was able to walk again, and before I returned to work. I had been sent on an errand by my father to a village on the other side of our mountain. I was on the return journey and I could see most of Lake Maggiore spread before me when I heard an aeroplane and saw it as a distant dot in the sky. It got louder and louder and I got the impression that it was coming straight for me. Being machine gunned from the air was not unusual so I didn’t think it strange or question why I should be singled out, I just dived into the side of the road. The plane seemed to fly inches above my head, its engine screaming, but it was probably some fifty feet up. As I crouched in the culvert it went straight on and crashed into the mountain side within seconds, perhaps a hundred yards beyond me. I was so inured to war by then that I didn’t even bother to go and look at it but just got up and carried on home. When I got home I was told that an airman had bailed out further down the lake, but I didn’t see him.

Working for food

Now there came an added torment for us. We could not get salt. At first animal rock salt was consumed, then empty barrels of salted fish were either soaked or scraped, finally there was none at all. People suffered from recurring headaches; normally even if you do not sprinkle salt on your food there is plenty in it added as a preservative. The entire area was completely and totally without salt. To add to the misery, the winter of 1944 was the coldest ever. The temperature in the Po valley fell to an unprecedented minus 16 degrees centigrade. It had been bitterly cold in 1941, but this was far worse and all fuel had been used up.

After my foot healed I didn’t return to the factory. My father arranged for me to work and live with Angiolin Isabella, work in return for food. Angiolin was the wealthiest man in the village. He owned a pair of oxen, used for hauling cartloads of wood and other goods, a mule, several cows, and sheep and goats. I had to tend to these animals, feeding, milking, cleaning out. Angiolin also owned a tavern in San Michele, the place where Benedetto Isabella was pointlessly shot. This was another small hamlet, like San Martino, it was left deserted through the winter and only inhabited from spring to early autumn, when cattle and other livestock were taken up to the mountain summer pastures.

Angiolin was caught in his tavern in San Michele by Germans and fascists and accused of having delivered a load of bayonets (from when the barracks were looted in 1943) to the partisans. They smashed all his bottles outside then made him take his boots off and run up and down the broken glass as a German flogged him to force him on. Having wrecked the place, they stole his pig. He never quite fully recovered from this and it was one of the reasons he needed help with his work.

On 25 April 1945 there was a general insurrection throughout the province. I remember walking up the steep road from Porto to Musadino when suddenly a group of armed young men came racing down on bicycles. They were clearly partisans, but I had never seen any in broad daylight before like this. I remember I shouted something like ‘Porto’s full of Germans’ and they yelled back ‘We know!’ The Germans surrendered later that day and were permitted to leave, but there was a wave of executions, mainly by hanging, of prominent local Fascists. I do not remember any being hung in Porto but the local paper reported that about a dozen had been strung up in Luino, one dragged out of a car taking him to the gallows and beaten up by the enraged populace. No one was yet sure if this was the end or whether the Germans would return. The opposite side of lake Maggiore, the Piedmontese side, had been liberated by partisans for a month or so but had been constantly shelled by the Germans and Fascists from our side of the lake. So being freed by partisans was no indication that the war was over.

I returned to work with Angiolin. A few days later I was up in the mountains near San Michele when suddenly the bells in the valley started to ring out, village after village joining in, a great sound of bells. I knew at once that it was over and I could not believe that I had survived it, a lot of my friends hadn’t, not shot but through disease and malnourishment. I raced down the mountain. As I came to the first villages people were out laughing and cheering, then I got to Musadino and home. My mother was overjoyed. She told me that my father wanted me to go to Porto to join him, she said he was with the South Africans. I left at once, racing down to the lake side.

Meeting the South Africans

I had not seen my father for about three months. In Porto I found the lakeside full of Allied soldiers. I approached one and I asked ‘Do you know Peter?’, both my dad and I are called Peter (in Italian he was Pietro and I am Piero). I still after all these years remember his answer. He said ‘There’s a Peter in every station son’.

Finally I found him, the first thing he did was to take me to the kitchen. That evening, by the lakeside, seated with South African soldiers, he told me that Mussolini had been shot and strung up in Piazzale Loreto in Milan.

Most British people are shocked at Mussolini’s end, not knowing the full history of Piazzale Loreto (Loreto Square). In that square there was a burnt out garage and on that spot, on the morning of 10 August 1943, 15 men were shot by the Germans and Fascists and their bodies piled up in a heap one on top of the other. They are: Andrea Esposito, Domenico Fiorani, Gian Antonio Bravin, Giulio Casiraghi, Renzo del Riccio, Umberto Fogagnolo, Tullio Galimberti, Vittorio Gasparini, Emidio Mastrodomenico, Salvatore Principato, Angelo Poletti, Andrea Ragni, Eraldo Soncini, Libero Temolo, and Vitale Vertemati. The youngest was 21, the oldest 46. These are forgotten names that deserve to be remembered. Their bodies were piled up in a heap on display but relatives were forbidden to pay any last respects to them. The Fascists guarding the bodies and preventing access to relatives, are on record as spending the day laughing and joking at the ‘pile of rubbish’. The man who ordered this massacre was the Nazi security chief, Teodor Emil Saevecke.

These 15 are now known as the martyrs of Piazzale Loreto. Some were badly tortured, and the partisans vowed then that that is where Mussolini and 14 of his cronies would be hung alive or dead. When Mussolini was informed of the massacre by the Germans he is reputed to have said, ‘We shall pay dearly for this blood’. It was Teodor Emil Saevecke who also ordered the execution of 53 Jews at Meina, on Lake Maggiore, in September 1943. After the war he led a tranquil life in Germany despite all attempts to bring him to justice, and it wasn’t until the 1990s that he was jailed for life.

In his otherwise excellent ‘History of the Second World War’ (Penguin, ISBN: 0140285024), Peter Calcovoressi states that no South African soldiers served outside of Africa. In this he is wrong. The troops who arrived in late April 1945 in Porto Valtravaglia were the Battalion of Imperial Light Horse and Kimberley Regiment, the ILH-KR, they formed part of the 6th South African Armoured Division. I was with them from April 1945 until their embarkation for home in August 1946.

In mid-1945 the partisans were called upon to disarm to try to stop the bloodbath, by then some 30,000 Fascists had been executed (the official figures are 19,801 fascists shot or hanged from 25 April 1945, against 45,191 partisans and anti-fascists hanged and shot by the Nazis and Fascists in 1943/44) and it was not know what their reaction would be. No chances were taken and the South Africans were put on full alert. I managed to get myself smuggled into a half track and we went to a big sports field outside of Milan. My father didn’t know I was there. There I saw hundreds of partisans lined up armed, with South African troops, mostly out of sight, surrounding them. There were speeches on both sides, my father acting as interpreter. Everything went smoothly and the partisans peacefully laid down their arms and marched off with flags flying.

Later in 1945 the ILH-KR battalion was transferred to Spotorno, a really lovely spot on the Italian riviera, the rest of the 6th South African Division remaining in the Luino area. I and my father went with them. I travelled to Milan in a jeep. There I saw why we had had all those refugees. The city looked devastated. From there I travelled in the back of a 3-ton lorry. Nearly every bridge was destroyed and we often could only get up steep escarpments by going up in reverse at about 2 miles an hour. The journey seemed endless, but the devastation I saw made me realise how lucky we had been that the war had ended before the front line reached us. Just after Christmas 1945, the battalion left for home having fought its way up from southern Italy to Florence. I had formed deep friendships by then. My father and I were taken back to Musadino in a 15cwt truck laden with tinned food and gallons of South African brandy. After a month or so my father returned to work at the factory, but I became a civilian batman to two South African officers in Luino and Varese. After all that had happened it was like living in heaven.

There was one final thing. In August 1945 I was at a dance in Luino. The South Africans stopped the dance to announce that an atom bomb had been dropped on Japan. I was asked to go on stage, where the band were, and to make the announcement in Italian. I was deeply confused and embarrassed as I did not know what an atom bomb was in Italian, having never heard of one, I mumbled to cheers that a big bomb had been dropped. Some bomb!

Back to England

In late 1946 I returned to England with my father’s aunt, Esther Maturi, who had come to visit relatives and to collect me. I remember crossing into Switzerland and stopping in Basle. There the city lights at night utterly amazed me as did the shops full of chocolate and luxury goods. I had completely forgotten what a normal city looked like. The journey from Basle to Calais took three days, most of the bridges were destroyed in France and we slowly crossed temporary Bailey bridges. We arrived in Dover, where my British emergency passport was taken from me. Many years later when I myself was an officer in the Immigration Service, I used to think back to that time and to the two British officers who I now know were Special Branch.

My mother returned with my sister Gloria in 1947, and later that year she was joined by my father. I could not settle, and in 1948 I joined the army serving in Germany and the Far East as a regular soldier in the Royal Artillery. I left the army in 1953, and in 1956 joined the Civil Service, finally entering the Immigration Service in 1965, serving eight years as an Immigration Officer in Folkestone, then eight years as a Chief Immigration Officer at Terminal Two, and finally as an Inspector of Immigration at Terminal 3, Heathrow. I retired in 1987.

In the Introduction to his book ‘War In Italy 1943-1945 — A Brutal Story’, Richard Lamb states that ‘In the north… the Germans imposed a regime of terror; arbitrary arrests were common, with wide-spread executions of innocent people. However, living conditions were tolerable: there was enough food and inflation was kept down, while work was available in the industrial zones. In the southern part occupied by the Allies there was starvation, because the British and Americans could not spare enough shipping to feed the population adequately and production of home grown food was limited.’ This most certainly was not the experience of the north, in the Valtravaglia area. Non-military transport was almost non-existent and the Germans who, I agree, ‘imposed a regime of terror’ cared little, so far as I could judge, about providing or ensuring that ‘there was enough food’ — on the contrary, German requisitions of livestock were quite common. My hunger, and that of many like me, was real enough.

As for the fate of another in this story. Giuseppe Bastianini, the Italian Ambassador who had taken an interest in my plastered broken arm in 1940, became governor of Italian occupied Dalmatia. He then succeeded Ciano as Foreign Secretary. In July 1943 he voted for the Grandi motion which led to Mussolini’s fall. In early 1944 he took to the mountains, a wanted man by Germans and Republican fascists. At the Verona trial of Ciano and others in 1944, he was condemned to death in absentia but managed to cross the mountain border to safety in Switzerland. In 1947, having returned to Italy, he was arrested living incognito in Calabria and put on trial in Rome for his Fascist past, but absolved and acquitted. He died in Milan in 1961. In 2003 he was honoured, along with other Italian Fascist diplomats and military personnel, in the Israeli documentary ‘Righteous Enemy’, screened at the United Nations, for his part in saving over 40,000 Jews in Yugoslavia, whilst he was governor of Dalmatia, by issuing false documents and helping them get to Switzerland.

I went back to Musadino in 1967 for a short visit. Much had changed. The cobbled streets were tarmacked, and the roads were full of Lambrettas and Vespa scooters. Many villagers were now working in Milan or Varese, commuting daily. Nearly everyone now spoke formal Italian, and Lombard dialect was almost non-existent. The oxen too had disappeared, a forgotten memory. The house now had running water and a toilet. It was now used as a summer vacation home by my French relatives. The fountain tap in the square was still there, but many were amazed when I told them that it had been our sole source of water for five years. Many of the old people had died and the war seemed a world away. Even the Germans had returned, but now as welcome tourists.

Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk